“Someday They’ll Eat Grass”: The Launch of Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby as Seen in the Boston Herald and other American Newspapers

The latest Hollywood version of The Great Gatsby has sparked book sales of more than a million copies in the first half of 2013 alone. That's more than twice the number typically sold in a full year, and far more than the small number sold between 1925 and 1940—the year a dejected Fitzgerald died at 44. In May 1925, a month after Charles Scribner’s Sons released Gatsby to mixed reviews, Fitzgerald wrote to Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins about its reception: “I think all the reviews I've seen, except two, have been absolutely stupid and lousy. Someday they'll eat grass, by God!”

In the 1925 pages of the Boston Herald—one of America’s oldest daily newspapers and winner of eight Pulitzer Prizes—one can closely follow the Gatsby launch, including Scribner's supporting advertising campaign.

Fitzgerald’s name first appears in the 1925 Herald on March 4—a month before Gatsby’s publication on April 10—within an advertisement for a now-forgotten Jazz Age novel:

The first prepublication announcement for Gatsby appears in the Herald on March 21:

Two forthcoming Scribner's books—Fitzgerald’s new novel and a Ring Lardner collection—are noted in the Herald on April 8, two days before Gatsby’s publication date:

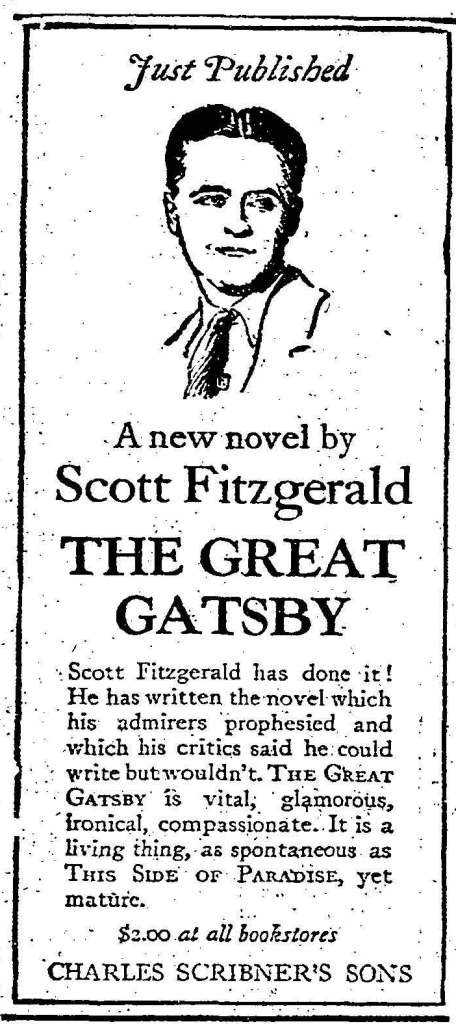

On April 11, the first Scribner’s ad appears in the Herald under a “Just Published” headline. The publisher’s ad copy reads, “Fitzgerald....has written the novel which his admirers prophesied and which his critics said he could write but wouldn’t...The Great Gatsby is vital, glamorous, ironical, compassionate. It is a living thing, as spontaneous as This Side of Paradise, yet mature.” The ad ran again on April 25.

A smaller ad ran in the Herald on May 2, placed near the page’s bottom right corner. It used the same image of Fitzgerald but featured an excerpt from an early appraisal published in The Saturday Review of Literature: “Certainly the best novel Scott has yet written. You can’t lay it down.”

The following day a major (and generally positive) piece by the influential critical and journalist H.L. Mencken, first published in the Baltimore Evening Sun, appeared in the Boston Herald. Mencken wrote in part,

Scott Fitzgerald‘s new novel, "The Great Gatsby," is in form no more than a glorified anecdote, and not too probable at that....The principal personage is a bounder typical of those parts—a fellow who seems to know everyone and yet remains unknown to all—a young man with a great deal of mysterious money, the tastes of a movie actor and, under it all, the simple sentimentality of a somewhat sclerotic fat woman....

This story is obviously unimportant, and though, as I shall show, it has its place in the Fitzgerald canon, it is certainly not to be put on the same shelf, with, say, "This Side of Paradise." What ails it, fundamentally, is the plain fact that it is simply a story—that Fitzgerald seems to be far more interested in maintaining its suspense than in getting under the skins of its people....

What gives the story distinction is something quite different from the management of the action or the handling of the characters; it is the charm and beauty of the writing...The story, for all its basic triviality, has a fine texture, a careful and brilliant finish. The obvious phrase is simply not in it. The sentences roll along smoothly, sparklingly, variously. There is evidence in every line of hard and intelligent effort. It is a quite new Fitzgerald who emerges from this little book and the qualities that he shows are dignified and solid. "This Side of Paradise," after all, might have been merely a lucky accident. But "The Great Gatsby," a far inferior story at bottom, is plainly the product of a sound and stable talent, conjured into being by hard work.

A new Scribner’s ad, smaller than the previous two, appeared in the Herald on May 9. The ad began with a two-word excerpt from a newspaper review, but continued in less-than-convincing fashion:

“Great Scott!” wrote Laurence Stallings at the head of his review of Scott Fitzgerald’s new novel in the New York World. The book delighted him, as it will you.

A fourth Scribner’s ad, even smaller than the previous three, appeared in the Herald the following week, now quoting an American author citing Mencken’s review, but no longer including the image of Fitzgerald.

Still smaller was a fifth Herald ad, printed the next week on May 23, again without Fitzgerald’s image, but now briefly quoting a Town and Country magazine review: “Approaches perilously near a masterpiece.”

Several of the other reviews that so dismayed Fitzgerald can be found in American Newspaper Archives. On May 10, in a four-part Dallas Morning News series titled, “Prophets of the New Age,” Harvey Eagleton wrote:

And there is the weakness of the book, of all Fitzgerald’s books, the weakness that prevents them from ever being more than “popular fiction” of the most ephemeral variety....The omission of the constructive in Fitzgerald’s work is an indication of his fundamental lack of imagination, for in spite of all his cleverness, and his wit, he has no creative faculty....

One finishes “The Great Gatsby” with a feeling of regret, not for the fate of the people in the book, but for Mr. Fitzgerald. When “This Side of Paradise” was published, Mr. Fitzgerald was hailed as a young man of promise, which he certainly appeared to be. But the promise, like so many, seems likely to go unfulfilled. The Roman candle which sent out a few gloriously colored balls at the first lighting seems to be ending in fizzle of smoke and sparks.

On May 23, a review in the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that Scribner’s was now attempting to use Gatsby’s mixed reviews to some marketing advantage:

The publishers have just sent out a collection of conflicting opinions from advance notices of this book, and entitled it “The Fitzgerald Controversy.”

There is no controversy: the quoted reviews merely prove that some like Fitzgerald and some do not. And it may be remarked that it will make little difference in your status in intellectual society whether you are on admirer or a despiser of “The Great Gatsby.” It is not a great novel; on the other hand, it is not a despicable one.

Written by the Plain Dealer’s literary editor Edward “Ted” Robinson, the review ends:

Therefore this book consists of Fitzgerald cleverness. So do Fitzgerald’s other books. And perhaps the author can go on to the end of his career making books out of cleverness. But if he does, the end of his career will be preceded by the end of his fame.

In the New Orleans Times-Picayune’s “Literature and Less” column, critic John McClure wrote in part:

“The Great Gatsby”...Mr. Fitzgerald’s new book and probably his best, is one of the cleverest books of the year. That is what is the matter with it....He makes clever remarks, some spontaneous, many smacking of the notebook, to such an extent that you lose the sense of unity demanded in a work of literary art. Worse, he is so addicted to the use of Wednesday-and-Thursday terms (words which mean something this week but may mean something else before fall, new words that everybody is using, just as everybody hums the momentary popular song) that the style is raw. The use of new words—colloquialisms or slang—is difficult. Unless they are used with consummate skill they are as objectionable as new paint, slick, shining, crude and glaring....

Mr. Fitzgerald is still where he was five years ago.

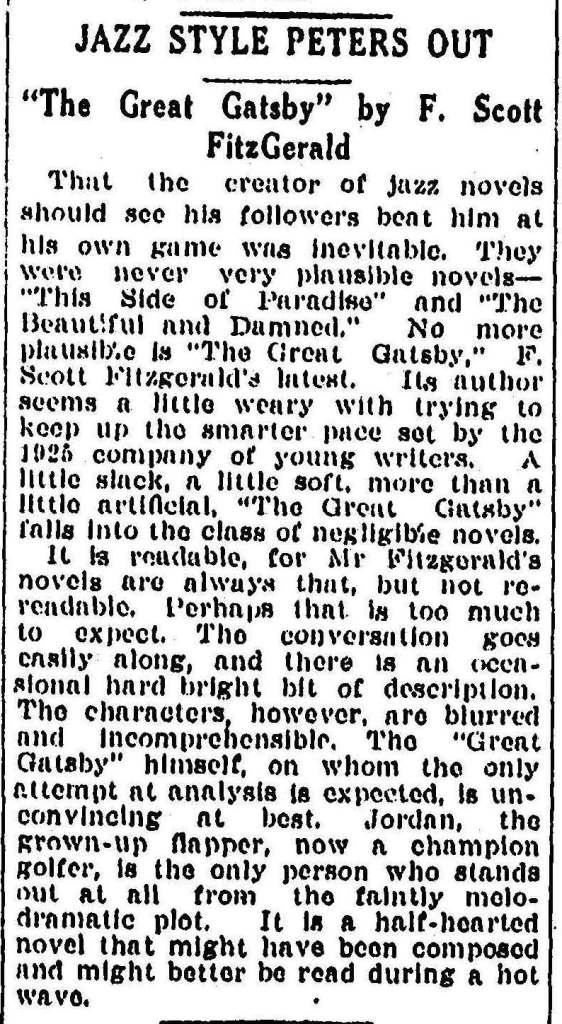

Another poor review appeared on July 5 in the Springfield Sunday Republican. Headlined, “Jazz Style Peters Out,” it stated,

That the creator of jazz novels should see his followers beat him at his own game was inevitable. They were never very plausible novels—“This Side of Paradise” and “The Beautiful and the Damned.” No more plausible is “The Great Gatsby,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s latest....A little slack, a little soft, more than a little artificial, “The Great Gatsby” falls into the class of negligible novels.

It is readable, for Mr. Fitzgerald’s novels are always that, but not rereadable.

Writing to his friend Edmund Wilson in 1925, Fitzgerald lamented that “of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.” He died 15 years later, never knowing the critical recognition and commercial success that followed. During World War II, The Great Gatsby was one of the paperbacks selected by a group of publishers for distribution to soldiers, sparking a fresh look at a work many regarded as a Jazz Age relic.

Appreciation continued to build in the following decades. During the 1950s, Gatsby began to be taught in most American high schools, and in 1960 critic and Fitzgerald biographer Arthur Mizener declared it “a classic of twentieth-century American fiction.” In addition to film, Gatsby has been adapted for opera, theater, ballet and even computer games. Today, Gatsby is Scribner’s bestselling book.

Learn more about Early American Newspapers and other Readex newspaper collections.