“Toward That Crooked Path”: Early Motion Pictures Said to Induce Criminal Behavior in Impressionable Viewers

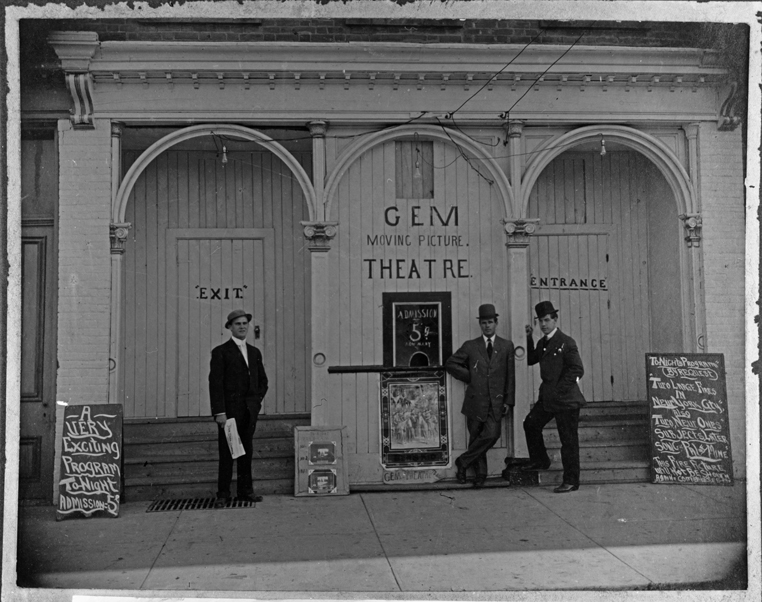

The advent of motion picture industry at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries was explosive. The American public was besotted by the astonishing and cheap new entertainment. From the earliest days, the movies provoked great excitement, both enthusiastic and alarmed. Enthusiasts saw previously unattainable opportunities to use this medium to educate and uplift, and to open a wider world to the patrons in the seats. Alarmists predicted a pernicious influence which would hasten the demise of morals and acceptable behavior, particularly among impressionable youth.

An early instance of the motion pictures inspiring criminality in a youngster was reported by the San Jose Evening News on December 12, 1905.

A “seventeen year old lad arrested at Coney Island for making counterfeit dies, became inspired with the idea to have a real counterfeiter’s den by moving pictures he saw…”

Over time these sorts of reports became a regular feature in the popular press. They featured juvenile criminals as young as a boy of 10 who said “he was taught to be a burglar by going to a moving picture show where he saw pictures which showed train and bank robberies. He went home, he says, with a desire to become a great robber.” The Grand Rapids Press ran the story on August 8, 1906.

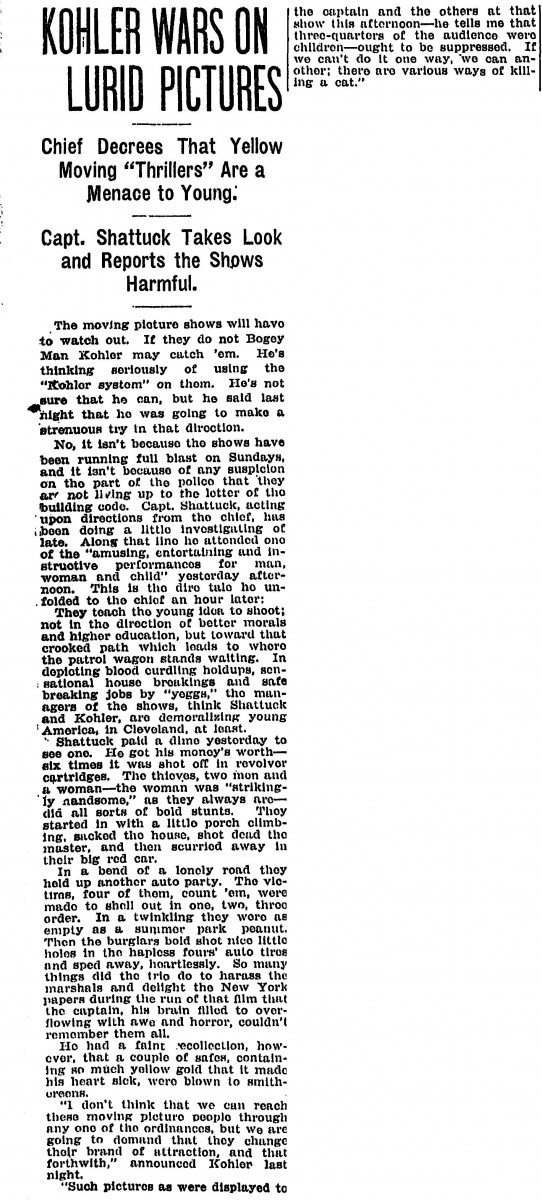

There were early calls for censoring movies, particularly from municipal officials. Cleveland’s Chief of Police was ardent in his determination to suppress what he called “yellow moving ‘thrillers.’” On December 23, 1906, the Plain Dealer reported Chief Kohler’s war “on lurid pictures.” The reportage is rather wry.

The moving picture shows will have to watch out. If they do not Bogey Man Kohler may catch ‘em. He’s thinking seriously of using the “Kohler system” on them. He’s not sure that he can, but he said last night that he was going to make a strenuous try in that direction.

The chief sent Captain Shattuck to investigate. After seeing a show described as “amusing, entertaining and instructive performance for man, woman and child,” he reported to the chief that

They teach the young…to shoot; not in the direction of better morals and higher education, but toward that crooked path which leads to where the patrol wagon stands waiting. In depicting blood curdling holdups, sensational house breakings and safe breaking jobs by “yeggs,” the manager of the shows, thinks Shattuck and Kohler, are demoralizing young America, in Cleveland, at least.

There follows a vivid account of a gang of three including a “strikingly handsome” woman “as they always are” who “did all sorts of bold stunts.” At the conclusion of the article, Kohler, mindful that current ordinances may not allow him to suppress these shows, was upbeat: “If we can’t do it one way, we can another; there are various ways of killing a cat.”

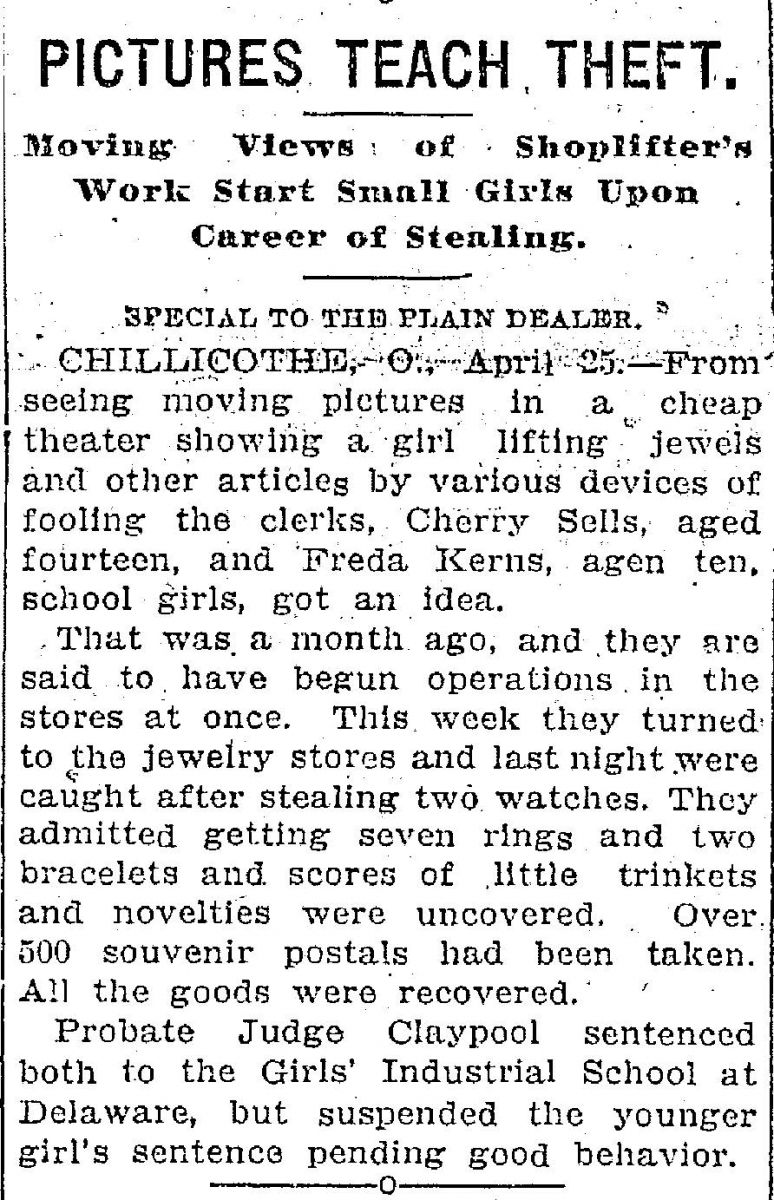

Girls also appear to have been influenced by the moving pictures. On April 26, 1907, the Plain Dealer ran a story which began:

From seeing moving pictures in a cheap theater showing a girl lifting jewels and other articles by various devices of fooling the clerks, Cherry Sells, aged fourteen, and Freda Kerns, age[d] ten, school girls, got an idea.

That was a month ago, and they are said to have begun operations in the stores at once.

They had accumulated rings, watches, bracelets “and scores of little trinkets and novelties”. They were sentenced to the Girls’ Industrial School, but the judge “suspended the younger girl’s sentence pending good behavior.”

The Plain Dealer spilled a lot of ink in reporting aberrant behavior inspired by patrons of the movies. A headline in the November 21, 1907, issue blared “THINKS HE’S AN OUTLAW. Excited by Realism of Moving Pictures, Man Imagines He is a Desperado.” The 24-year old man “drove the audience in a moving picture show…headlong into the street, assaulted the ticket taker and started to break up the furniture.” He was imitating Red Eye Dick, a cowboy known as the Kansas terror.

[He] had a half nelson on G.M. Wesley, ticket taker, and was giving a vivid exhibition of how a finger could be used in place of a bowie knife when Patrolmen Butcher and Bitzer interfered.

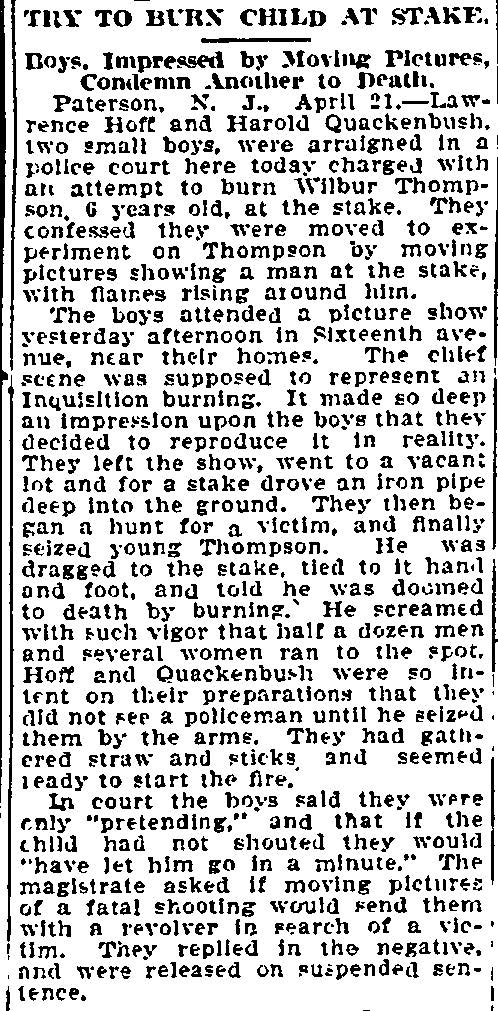

The public appetite for such reports must have inspired the Bellingham Herald to run a story from Paterson, New Jersey, on April 21, 1909: “Try to Burn Child at Stake. Boys, Impressed by Moving Pictures, Condemn Another to Death.” The victim “screamed with such vigor that half a dozen men and several women ran to the spot.” The boys “were so intent on their preparations that they did not see a policeman until he seized them by the arms. They had gathered straw and sticks and seemed ready to start the fire.” The terrified boy was saved.

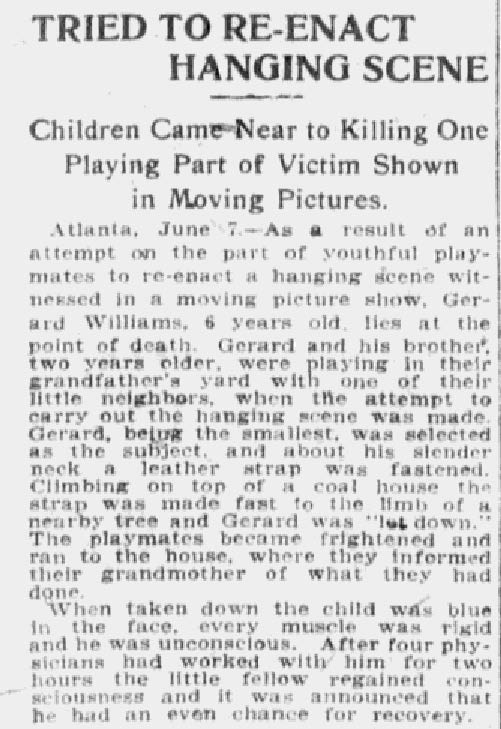

Other life-threatening events occurred which were attributed to the influence of the movies. The Boston Journal on June 8, 1909, reported that

As a result of an attempt on the part of youthful playmates to re-enact a hanging scene witnessed in a moving picture show, Gerard Williams, 6 years old, lies at the point of death….

When taken down the child was blue in the face, every muscle was rigid and he was unconscious. After four physicians had worked with him for two hours the little fellow regained consciousness and it was announced that he had an even chance for recovery.

A less fortunate child lost her life as reported by the Oregonian on July 19, 1909. “Frances Lord, aged 3, was shot and killed tonight by a 10-year-old boy who was imitating the picture of a desperado he had seen in a moving-picture show.” The boy had obtained “an old army musket and was making the children in the neighborhood hold up their hands….The little girl was playing in front of her home and not understanding his command, the top of her head was almost blown off.”

The Plain Dealer appears to have had a particular interest in publishing any account of bad behavior ascribed to the movies. The newspaper reprinted an unattributed article from Pittsburgh on July 11, 1910, which began:

Two boys arrested at a cheap hotel here tonight are held in connection with the attempt to hold up a Mount Washington street car early this morning when Police Lieutenant Shriver Stewart, who was on the car in citizen’s clothes, was probably fatally shot while trying to stop the boys in their robbery.

The “boys” were 18 years old and cousins. One of them confessed that they had been inspired by seeing “a moving picture show of a western train robbery yesterday afternoon, and when they left the show they went to a pawnshop and bought a revolver.”

Many plans were brought forward to censure the movies, or impose an age limit based on the content. This possibly legitimate concern was taken up and expanded by Pecksniffians who agitated for no kissing, “No elopements, Spooning, Robberies or Fights if Endeavorers Win” in Missouri as reported by the Pawtucket Times on July 21, 1910. The crusade was undertaken by the Christian Endeavor Union of Missouri.

In August 1910 an unsubstantiated story was printed by several newspapers, including the Aberdeen Daily News which headlined the account: “Moving Pictures Cause Crime, Denver Woman Incited by Picture of Crime, Shoots and Kills Husband.” And, then shot herself: “The police say the crime was the result of seeing a moving picture show depicting the killing of a girl as she slept, and the murder was suggested by the show.” How they knew this is not revealed.

Cleveland seemed bound to polish its repressive reputation as reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer on December 31, 1910. The headline: “Deaf Mutes Say Moving Pictures Use Profanity. Lip Reader Declares Characters Use Vile and Indecent Language.” The article referred to

Mrs. Elmer L. Bates, for many years a teacher of the deaf and dumb and an expert in the art of lip reading, [who declared] that these shows are the chief sources of amusement for the deaf and they are prevented from enjoying them because they are able to understand what is being said by the characters on the screens. Mrs. Bates made a tour of the downtown shows yesterday, accompanied by a reporter, who wrote down the picture talk, and at times the language was so vile that she had to stop.

While “cowboy and Indian” films were sometimes faulted for inspiring juvenile misadventure, neither some Indians nor cowboys, or at least their employers, were happy about the effect these movies had. The February 18, 1911, issue of the Baltimore American printed the headline “Indians Don’t Like It. Aroused Over Way They Are Shown In Moving Pictures.” Perhaps the reportage was tinged with racism.

Indian chiefs now visiting the lodge of the White Father have voiced emphatic protests to the base uses to which their race is put in the unwritten literature of the five and ten cent picture shows, and Commissioner Robert G. Valentine has promised to take the matter up in all seriousness if necessary with the White Father himself.

At the same time, ranchers were complaining that “Moving Pictures Spoil the Cowboy” as published by the Duluth News-Tribune on March 14, 1911.

Film makers demand their services and pay them handsomely for riding bucking horses in front of the moving picture camera or for taking part in an alleged ‘western drama’….

The old ranchers are sore and ill conceal their hostility. They declare that pictures only make ornery cowboys and give easterners wrong ideas of life in the cattle country.

It seems that the Indians had a point. The Montgomery Advertiser somewhat breathlessly headlined a story on March, 3, 1912 “BABY FRIGHTENED: DIES, Visits Moving Pictures and is Taken Home Screaming in Fear.” A three-year-old “had hysterics after returning home, resulting yesterday in his death. He was quieted after returning home, but later began screaming about the ‘Indians.’”

So, children were turning to crime, babies were dying of fright, mad men were going berserk, wives were murdering husbands all because of moving picture shows. Meanwhile more and more Americans were swarming to the cinemas. There must have been uncountable adults and children who attended these entertainments and did not become corrupted, but there was little in it so far as the press was concerned. It was much more titillating to report bad behavior as did the Kansas City Star on January 10, 1913, which thought it newsworthy to announce “SUNDAY SCHOOL GIRLS ROB. Moving pictures influenced four young Denver misses.” Apparently, these girls “ranging in ages from 8 to 10 years…have been robbing fashionable homes in Denver in the last two months.” The girls told the judge that they were inspired by the movies. The presiding judge opined:

This is the worst case of immorality among children I have ever had come before me. I am surprised and all the more so since these girls’ parents are fairly well to-do people, and they tell me that they go to Sunday School every Sabbath. It is another case of the depraving influence which motion pictures or any suggestive action of such a nature can have upon the childish mind.

The efforts to report the harmful effects of the movies combined with the forces of moral censure would beset the film industry for many years to come.

Learn more about Early American Newspapers, Series 1-16.