Surviving the Titanic: The Stories Behind the Story

No novelist would dare to picture such an array of beautiful climatic conditions—the rosy dawn, the morning star, the moon on the horizon, the sea stretching in level beauty to the skyline—and on this sea to place an ice-field like the Arctic regions and icebergs in numbers everywhere—white and turning pink and deadly cold,—and near them, rowing round the icebergs to avoid them, little boats coming suddenly out of the mid-ocean, with passengers rescued from the most wonderful ship the world has known.

—Lawrence Beesley, The Loss of the S.S. Titanic (June 1912)

The Titanic. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

In the hours after the Titanic sank, the press was faced with the task of telling a story about what had been thought impossible—the sinking of an unsinkable ship. Without substantive information—before the rescuing Carpathia returned to the United States—news bureaus around the world started running speculative accounts about the disaster.

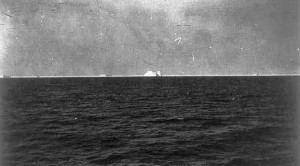

View from the Carpathia of iceberg that sank the Titanic. Source: Library of Congress

For four days, as the Carpathia sailed to New York from the site of the sinking, carrying her original vacationing passengers and newly boarded Titanic survivors, three men—each instrumental to our knowledge of the event today—were embedded in one of the century’s most shocking stories: Arthur Rostron, English captain of the Carpathia; Lawrence Beesley, English scientist and Titanic survivor; and Carlos Hurd, an American reporter and Carpathia passenger who had been on vacation with his wife. Their sense of the tragedy, and their response to the news world during the days that followed, show us the different ways that individuals define and experience extreme trauma. In all of his years at sea, Arthur Rostron, 40 years old, had never needed to respond to a distress call. He had 23 years of naval experience, but was captain of the Carpathia for only three months when he was roused by Harold Cottam, his ship’s radio operator, in the early hours of April 15, 1912. Cottam awoke an annoyed Rostron in his cabin to convey the frantic QCD (or Quick Come Distress) call from the Titanic: “Hurry. Hurry! …. “sinking by the head.”

Carpathia Capt. Arthur Henry Rostron. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

Captain Rostron responded immediately—moving full speed ahead toward the accident site. By the time the Carpathia arrived at the Titanic’s last reported location, Rostron had organized his ship and readied its passengers for the hysteria he anticipated. Electric lights were rigged along the Carpathia; gangway doors were opened; pilot ladders, nets, and ropes were ready to be dropped; hot drinks, soup, warm clothing, and blankets were on deck. Cargo cranes were ready to haul in the mail and the passengers’ luggage. The three doctors on board were set up at first aid stations in the ship’s dining rooms. Rostron made sure Carpathia passengers would be segregated from Titanic survivors. He established a check-in process to create adequate documentation as survivors boarded. He told his crew to drink coffee before they had reached the disaster, warning it was going to be a long night ahead. Starting at 2:45 a.m., Rostron had the Carpathia blast “encouragement rockets” every 15 minutes to signal Titanic passengers and crew that help was on the way. At 4:00 a.m., arriving at the Titanic’s last reported position, Captain Rostron stopped the Carpathia, shut down its engines—and felt sick. He saw nothing. No ship. No lights. No lifeboats or passengers. Nothing. Moments later, however, he spotted a dim green light on the horizon—a lifeboat with two passengers aboard. As the first survivor boarded the Carpathia, she confirmed to the stunned crew the shocking, horrific truth: the Titanic had sunk. As daylight broke, several lifeboats and a number of icebergs filled Rostron’s view. With icebergs visible in every direction, Rostron, a religious man, would later look back at the Carpathia’s speedy rescue dash and say that he, like the captain of the Titanic, was moving dangerously fast through the icebergs that morning, and the only thing to save his ship from being sliced open like the Titanic was “the hand of God.”

From the Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 17, 1912. Click to open full article. (Source: America's Historical Newspapers)

Lawrence Beesley, the rescued English scientist who had been a second-class Titanic passenger, described the morning of April 15 in his memoir The Loss of the S.S. Titanic:

As far as the eye could reach to the north and west lay an unbroken stretch of field of ice, with icebergs still attached to the floe and rearing aloft their mass as a hill might suddenly rise from a level plain. Ahead and to the south and east huge floating monsters were showing up through the waning darkness, their number added to moment by moment as the dawn broke and flushed the horizon pink. It is remarkable how “busy” all those icebergs made the sea look: to have gone to bed with nothing but sea and sky and to come on deck to find so many objects in the sight made quite a change in the character of the sea: it looked quite crowded; and a lifeboat alongside and people clambering aboard, mostly women, in nightdresses and dressing-gowns, in cloaks and shawls, in anything but ordinary clothes! Out ahead and on all sides little torches glittered faintly for a few moments and then guttered out—and shouts and cheers floated across the quiet sea. It would be difficult to imagine a more unexpected sight than this that lay before the Carpathia’s passengers as they line the sides that morning in the early dawn…

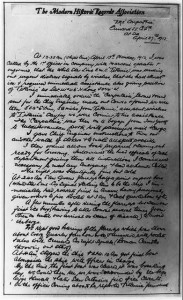

Photocopy of handwritten account by Captain Roston. Source: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

By 8:30 a.m., with survivors on board and their lifeboats hauled on deck, Captain Rostron surveyed the exact site of the Titanic’s descent. All that remained of the once marvelous, unsinkable ship was a dense litter field of floating debris. Rostron asked an Episcopalian minister aboard to lead a service that morning—a prayer “out of respect to those who were lost and of gratitude for those who were saved.” In over four hours of searching the vicinity, Captain Rostron saw only one body floating on the ocean’s surface. Earlier that morning, Carlos Hurd, an American news reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and his wife were second-class Carpathia passengers, traveling on vacation from the U.S. to Fiume (now Croatia). Hurd was awakened by a strange feeling. His cabin was cold, and the Carpathia was not moving. Confused by the silence of the engines and the clamor of hallway voices, he decided to investigate. He walked to what was the dining room the evening before but that morning appeared to be an infirmary. A Carpathia crewmember, pointing to a disheveled group of shivering refugees in the makeshift hospital, broke the news to Hurd: “From the Titanic; she’s at the bottom of the ocean.”

Carlos Hurd. Source: Missouri History Museum

From the Carpathia’s deck, Hurd then saw a number of approaching lifeboats filled with traumatized survivors. As they boarded—numb and in shock, and searching for loved companions—Carlos Hurd stopped his vacation and got to work. Finding any scraps of paper he could, he began to interview survivors, many of whom were devastated women and children. Immigrants whose life savings fell to the bottom of the sea, women who could not speak English, all now were being towed to a new world without the men who had been guiding their futures. Hurd wrote down their various, sometimes contradictory, accounts of the Titanic’s descent. One survivor said Titanic captain E.J. Smith was last sighted standing atop the sinking ship’s bridge, as her decks washed away, before jumping into the sea—with no life preserver evident—and swimming away from a rescue attempt. Another account claimed Smith had shot himself on board as the ship went down. Hurd wrote of both accounts. Yes, the Titanic’s string band played until the ship’s last moments. However, based on Hurd’s record of the sentiment of survivors, who, hearing the music, knowing the words of the last ballad—“So by my woes I’ll be, Nearer my God, to Thee”—some watching loved ones clinging to the rails of the sinking ship or flailing helplessly in the frigid sea—the music brought out more “strain” than relief. The combination of the music, the wretched groans of death, the beauty of the stars above, and the horrendous sight of the ship slowly ripping in two before sinking was too much to bear.

From the Salt Lake Evening Telegram, April 19, 1912. Click to open full article. Source: America's Historical Newspapers

From surviving Titanic quartermaster J.H. Moody, Hurd obtained some reasons for the accident. The Titanic had been moving full steam ahead, ignoring warnings from other vessels about the presence of icebergs. The trip was less a maiden voyage and more a race to reach New York in the best time. According to Moody, “…officers were striving to live up to the orders to smash the record.” In his account Beesley took issue with the way survivors were portrayed by the press, believing the scene on the Carpathia was intentionally over-blown for effect. He felt his own sense of the survivors’ states of mind was much more truthful than the press’s depiction:

Much that is exaggerated and false has been written about the mental condition of passengers as they came aboard: we have been described as being too dazed to understand what was happening, as being too overwhelmed to speak, and as looking before us with ‘set, staring gaze’ with the shadow of the dread event….scenes of women weeping and brooding over their loses hour by hour until they were driven mad by grief—all this has been reported to the press by people on board the Carpathia…the one thing that matters in describing an event of this kind is the exact truth…and my own impression of our mental condition is that of supreme gratitude and relief at treading the firm decks of a ship again.

From the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 19, 1912. Click to open full article. Source: America's Historical Newspapers

On board the Carpathia, Beesley and other Titanic survivors formed a committee to establish, among other things, a general fund for survivors from steerage, to present a loving cup to Captain Rostron, and to write a public letter suggesting better safeguards for ocean travel. Beesley felt it critical to accurately describe the accident—“to inform the English public”—and to bring perspective to the American press’s histrionic tendencies in reporting disasters:

It seemed well, too, while on the Carpathia to prepare as accurate an account as possible of the disaster and to have this ready for the press, in order to calm public opinion and to forestall the incorrect and hysterical accounts which some American reporters are in the habit of preparing on occasions of this kind. The first impression is often and most permanent, and in a disaster of this magnitude, where exact and accurate information is so necessary, preparation of a report was essential. It was written in odd corners of the deck and saloon of the Carpathia, and fell, it seemed very happily, into the hands of the one reporter who could best deal with it, the Associated Press. I understand it was the first report that came through and had a good deal of the effect intended.

As the Carpathia made its way back to its harbor with Hurd, Beesley, and the survivors on board, the fate of the Titanic was unknown to newsrooms around the world. A number of papers ran speculative accounts of what had happened: There was an accident, and the Titanic and all its passengers were being towed back to safety; the amazing Titanic sank but all on board were safe; the Titanic hit an iceberg and all passengers died at sea. Meanwhile, on board the Carpathia, Captain Rostron had forbidden his crew from talking to reporter Carlos Hurd. In addition, Hurd was not allowed to send his press dispatches via the ship’s wireless telegraph. In fact, although Rostron testified later that “absolutely no censorship” took place, much of the communication from the Carpathia was held back. In addition, messages to the Carpathia from the press on the mainland were intercepted.

From the Idaho Daily Statesman, April 19, 1912. Click to open full article. Source: America’s Historical Newspapers

Joseph Pulitzer, Hurd’s boss at the time, knew that Hurd was on board the Carpathia, and sent several radio messages to the Carpathia urging Hurd to interview Titanic survivors. Charles E. Chapin, city editor of New York’s Evening World, also knew Hurd was on board, and wanted to run Hurd’s first-hand story immediately upon the Carpathia’s return. Chapin had attempted to send a message to Hurd, asking the reporter to throw his dispatch from the ship’s deck to Chapin who would be in a tug boat in New York Harbor as the Carpathia arrived. Hurd never received any of these messages. In fact, Rostron had all messages intercepted and, in effect, had instituted a media blackout on his ship. Rostron apparently went so far as to confiscate all stationery aboard the Carpathia so that the reporter would be unable to capture accounts. Hurd was resourceful, using toilet paper, among other items, to write his story. His wife, who was also writing about the surviving women, took her husband’s scraps, accumulating shards of chronicles, which she brought to the bed in their cabin and sat on to avoid confiscation. On the evening of April 18, 1912, the Carpathia approached New York. By this time, Carlos Hurd understood he would never be allowed to leave the ship with his story. As the New York lights became evident in a storm-filled sky, a number of tug boats filled with reporters approached the Carpathia. Hearing Hurd’s name being called through a megaphone from a tug, the Carpathia’s officers ordered Hurd to stay away from the rails. Ignoring their command, Hurd wrapped his story in a cigar box, sealed it closed, and attached champagne corks to the outside. Spotting Chapin in a tug, Hurd chucked the cigar box over the side of the Carpathia towards the city editor, but the box became ensnared in guy wires securing a Titanic lifeboat to the Carpathia. A sailor aboard the Carpathia, watching the drama unfold, worked his way to where the boxed dispatch had been snagged, grabbed the box, and threw it on to Chapin’s tug to the cheers of the Titanic survivors.

From the Miami Herald, April 30, 1912. Click to open full article. Source: America's Historical Newspapers

Beesley also described the media’s presence as the Carpathia entered New York Harbor:

Surrounded by tugs of every kind, from which (as well as from every available building near the river) magnesium bombs were shot off by photographers, while reporters shouted for news of the disaster and photographs of passengers, the Carpathia drew slowly to her station at the Cunard pier, the gangways were pushed across, and we set foot at last on American soil, very thankful, grateful people.

Carlos Hurd’s 5,000 word chronicle was immediately published, as were his wife’s interviews with Titanic survivors. Many New York papers ran first-hand accounts of what had happened aboard the Titanic in special editions on the day of the Carpathia’s arrival in New York. Hurd’s notoriety as a dedicated journalist who stopped at nothing to write of the tragedy of the century followed him for years to come. Captain Arthur Rostron received a number of prestigious awards for his rescue dash to the Titanic survivors. And, two months after its sinking, Lawrence Beesley’s memoir, The Loss of the SS Titanic, was published. Beesley’s and Rostron’s apprehension about the role of the American press in such a major world event may have represented a general British regard for U.S. media. London, after all, was the hub of global news up until the sinking of the Titanic. Had the Carpathia picked up the survivors and brought them back to England, rather than New York, what would have become of Carlos Hurd’s story? Would Captain Rostron have been more cooperative about news dispatches coming and going to his ship if the correspondence to the Carpathia had come from London? Did New York newspapers become an established voice of international news simply because the Carpathia delivered the survivors of the Titanic to the news reporters of New York rather than London?

Lawrence Beesley in the Gymnastics Room of the Titanic

What is to be made of Lawrence Beesley’s sense that there was minimal drama in the immediate aftermath of the wreck of the century—an accident in which only 31% of those on board survived, and those survivors witnessed the stunning, horrific loss of so many lives? How could Beesley describe the response of survivors as reflecting “gratitude” and “relief,” without any prevalence of shock and hysteria on board the Carpathia? What effect does one’s cultural identity have on information portrayed—or not portrayed—during an epic international tragedy? Does a calamity really have an “exact truth,” as Beesley set out to provide in his memoir, or do multiple, disjointed, perspectives, such as those coming from Carlos Hurd, Captain Rostron, and Lawrence Beesley, give us a better understanding of the wreck of the Titanic and its aftermath?