“A Little Like Murder:” Telescopic Rifle Sights Alter the Course of the American Civil War

The telescopic sight is the small tube running along the top of the barrel.

It does seem a little like murder to pick off a man as one would a deer, but sharp-shooting in war is one of the “necessities.” The “Near Yorktown” correspondent of the New York Post relates the following:

Ever since our pickets have been within six hundred yards of the enemy’s work, a rebel seven footer has shown himself tauntingly at a safe distance from our guns, evidently braving the fire of our sharp-shooters. All the pieces had been repeatedly levelled upon him, but without effect. To-day he came outside as usual, waving his hat when two balls went whizzing toward him, but fell short. The rebel continued his observations. Meanwhile a messenger was dispatched for a certain telescope target rifle known to be in the hands of a sharp-shooter, and Colonel Berdan and one of his men walked out to see the result as one would go to a bear hunt. Arrived at the point designated, the seven footer was still there, when the owner of the rifle drew up at arm’s length, and the moment the muzzle fell as to cover his heart the trigger was touched and the taunting foe fell without a struggle. A skirmish ensued, our sharp-shooters trying to prevent the rebels from recovering the body, and it was finally left outside until nightfall.

It’s likely that Major General John Sedgewick knew exactly what hit him on May 9, 1864, in his final moments commanding the Union Army’s VI Corps. Sedgewick was out on a skirmish line during the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, in Virginia. Confederate sharpshooters’ bullets were whistling past his troops as he disparaged the shooters’ ability to hit anything intentionally. He was clearly going in harm’s way. If this brave, experienced officer had taken heed of the distinctive sound made by the peculiar hexagonal bullets, he might have lived to fight another day.

The senior-most Union officer killed during the American Civil War probably did not see the shooter who was about 800 yards away. But his assailant could see him. The Confederate marksmen were using scoped rifles at least one of which had been made by Sir Joseph Whitworth and imported from England at great hazard and expense. It was among the most deadly and specialized weapons of that era. Soldiers considered it an honor and a privilege to bear it and other target rifles like it.

An 1863 article entitled “The Whitworth Telescopic Rifle,” published in the Augusta Chronicle (Georgia), relates a passage from the Richmond Sentinel (Virginia) which bore testimony to the effectiveness of that weapon.

Selecting as a mark a crowd of officers and men gathered under a tree opposite to us, distant about 750 yards, I directed one of the men under my charge to aim carefully and fire at the centre of the crowd. The effect was startling. The sudden scattering of the crowd—the bearing off of a wounded man—the immediate concentration of the fire of the enemy’s sharp-shooters upon the spot from which the Whitworth had been fired—were gratifying proofs of the efficiency of the rifle.

Shortly after a regiment of the enemy crossed the Liberty Church Road, in full view, at a distance of about 1,300 yards. Eight or ten men left the ranks of the regiment; entered a garden on the road side, and began to help themselves to a “mess of potatoes.” While the Yankees were thus engaged, and had gathered together about some particularly productive spot, I directed Sergeant Hill to fire at them with the elevation required for 1,300 yards. The party left the garden precipitately, bearing off with them a wounded comrade, and in their haste forgot to carry off the potatoes.

Propaganda? A few lucky shots? Rather, skill and technology. From the Richmond Examiner in November 1863 we read another account of this remarkable weapon:

We have a wonderful gun in our army—the Whitworth rifle. It kills at two thousand yards—over a mile. It is a small gun, not larger than the Mississippi rifle. With a few of these rifles Longstreet shot across the Tennessee river, and drove the Yankees from the use of the river road by killing the teams and blocking up the road.

The Confederate Army was not unique in its utilization of advanced technology. The Union Army employed a variety of similar weapons. In 1861 Colonel Hiram Berdan began to organize elite corps of marksmen for service as sharpshooters—which didn’t necessarily mean that they were shooting rifles made by Christian Sharps although they eventually adopted the Sharps M1859 rifle and others. The term “sharpshooter” substantially predates the American Civil War and is related to the German Scharfschütze (sniper).

Volunteers for sharpshooter duty needed to pass a marksmanship test but were rewarded with tremendous autonomy and prestige within the ranks. They were exempt from routine camp duties and dedicated to pursuing high-value targets such as officers, artillery personnel and other snipers.

THE Governor and Council of New Hampshire having decided to raise two more companies of sharp-shooters for Berdan’s Regiments, the undersigned has been commissioned as Captain to recruit one of said companies, at its headquarters in Concord.

The best marksmen of the state are invited to enlist, after passing a satisfactory examination, and complying with the following test: Each applicant, when firing at a rest with a telescope rifle, at a distance of two hundred yards, to put ten consecutive shots in a target, the average distance not to exceed five inches from the center of the bull’s eye to the center of the ball.

Sharpshooters on both sides used a variety of weapons, often deferring to their personal rifles with which they were already familiar. Target rifles were typically much heavier than regular infantry arms and were shot from a rest such as a tree branch or earthen feature. They sometimes featured a sensitive second trigger and required special accessories to load and maintain. Artisanal weapons usually required non-standard ammunition that the shooters cast themselves. For instance, the bullets for the Whitworth were hexagonal to fit the unique barrel of that gun.

Some target rifles were muzzleloaders and time-consuming to reload; others were breech-loading arms that were more convenient and safer but required a high level of precision in their manufacture. A percussion target rifle might weigh up to thirty pounds and cost a great deal more than less refined weapons. But they made up for the care and expense by their deadly efficiency.

A key innovation in personal arms during the American Civil War was the use and refinement of telescopic sights. The Davidson scope featured on the Whitworth rifle was developed by British Lieutenant Colonel David Davidson following service in the Bombay Army in East India. The instrument was practical for military use by the mid-1850s, although Davidson had been perfecting it for decades prior to obtaining a patent in 1862.

With a more established manufacturing base than the Southern states, the Union Army used a number of domestically produced telescopic sights. The earliest practical design was developed around 1835 by John Ratcliffe Chapman of Oneida Lake, New York. Chapman was a civil engineer who was familiar with surveying instruments. He eventually collaborated with fellow gunsmith Morgan James of Utica, New York, to make the Chapman-James scope, a widely used design.

The scope below is mounted on a .40 caliber percussion rifle made by A.J. Plate of San Francisco. The brass scope is a version of the Chapman-James model made by Leander Amadon, a jeweler and competitive shooter working in Bellows Falls, Vermont. Amadon lived in the Connecticut River Valley a few towns south of Windsor, Vermont. Windsor was home to Robbins & Lawrence, defense contractors to the federal government and the first machinery company to mass-produce weapons using interchangeable parts through what became known as the “American System” of manufacturing. Water-driven machine tools such as those used by Robbins & Lawrence made the Industrial Revolution possible and became an essential component of Northern defense industries.

In 1855 William Malcolm began producing scopes in Syracuse, New York. His designs used combinations of lenses to focus colors correctly across the spectrum, resulting in a sharper image with a generous depth of field. The nearly three-foot lengths of nineteenth-century scopes mitigated the optical limitations of the instruments. Eye relief (the distance one’s eye needed to be from the eyepiece to see the target) was relatively short, so that sharpshooters frequently had black eyes caused by their rifle’s recoil driving the scope back into their heads with every shot.

Look closely at the image below of the 1st Massachusetts (Andrew’s) Sharpshooters. All of the guns visible are scoped. The instruments shown here featured magnifications ranging from about four- to twenty-power. Some scopes were constructed for the eyesight of a particular individual, while others could be adjusted by loosening set-screws and sliding internal lenses housed in brass cells.

When Andrew’s Sharpshooters weren’t posing for photographs, they were decimating Confederate forces:

The Telescope Rifle

A correspondent of the Boston Courier, speaking of this rifle says:

I have waited anxiously to learn the result in actual service, of the telescope rifles, which we are testing in the field for the first time, and I have very little doubt that hereafter they are destined to play an important part in warfare. I am happy to corroborate the testimony given by Gov. Andrew in their favor, by an extract from one of the sharp-shooters, who says:

“Our telescope rifles realized our best anticipations, maintaining all we have claimed for them. We can do good work at half a mile and some at a mile. A Mississippi Regiment, 1,500 strong, came in sight of us and although we were unsupported and only thirty of us in position to see them, we opened fire at over 100 rods (more than a quarter of a mile,) and our rifles fully met our expectations, doing fearful work, and soon putting the whole regiment to flight, while not one of their shots took effect.”

Reliable marksmen became famous within their respective armies and regions. Truman Head, known as “California Joe,” was a well-regarded sharpshooter who petitioned President Abraham Lincoln personally for discharge when his eyesight was damaged to the point where he could no longer serve. The illustration accompanying the anecdote below does not show him using a telescopic sight and is likely erroneous in that respect.

“California Joe” will always be remembered as the very apostle of sharpshooters. While before Richmond, a rebel sharpshooter had been amusing himself and annoying our General and some other officers by firing several times in that direction, and sending the bullets whistling in unwelcome proximity to their heads.

“My man, can’t you get your piece on that fellow who is firing on us, and stop his impertinence?” asked the General.

“I think so,” replied Joe; and he brought his telescopic rifle to a horizontal position.

“Do you see him?” inquired the General.

“I do.”

“How far away is he?”

“Fifteen hundred yards.”

“Can you fetch him?”

“I’ll try.”

And Joe did try. He brought his piece to a steady aim, pulled the trigger, and sent the bullet whizzing on its experimental tour, the officers meantime looking through their field glasses. Joe hit the fellow in the leg or foot. He went hobbling up the hill on one leg and two hands, in a style of locomotion that was amusing. Our General was so tickled—there is no better word—at the style and celerity of the fellow’s retreat, that it was some time before he could get command of his risibles sufficiently to thank Joe for what he had done.

Another famous Union sharpshooter was George H. Chase, known in the service as “Old Seth.” He shot a thirty-two pound telescopic target rifle made by George O. Leonard of Saxton’s River, Vermont. A story is related of a time when Chase virtually captured a Confederate cannon although he couldn’t physically take possession of the field piece.

There was an odd character among Berdan’s Sharpshooters, near Yorktown, known as “Old Seth.” He was quite an ‘individooal,’ and a crack shot—one of the best in the regiment. “His “instrument,” as he termed it, was one of the heaviest telescopic rifles. One night, at the time of roll call, Old Seth was non est. This was somewhat unusual, as the old chap was always up to time. A sergeant went out to hunt him up, he being somewhat fearful that the old man had been hit. After perambulating around in the advance of the picket line, he heard a low “Halloo!” “Who’s there? inquired the sergeant. “It’s me,” responded Seth, “and I’ve captured a secesh gun.” “Bring it in,” said the sergeant. “Can’t do it,” exclaimed Seth. It soon became apparent to the sergeant, that “Old Seth” had the exact range of one of the enemy’s heaviest guns, and they could not load it for fear of being picked off by him. Again the old man shouted, “Fetch me a couple of haversacks full of grub, as this is my gun, and the cussed varmints sha’nt fire it agin, while the scrimmage lasts.” This was done, and the old patriot kept a good watch over that gun. In fact it was a captured gun—or as good as that.

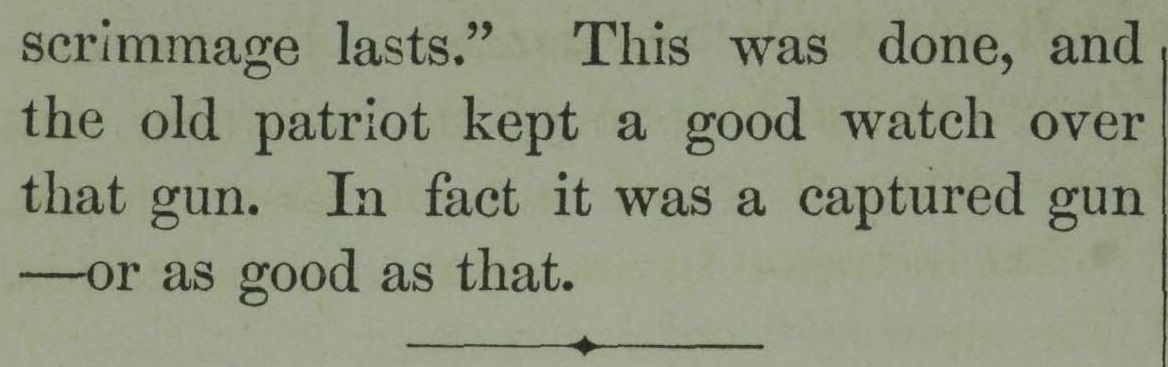

The Confederates had their own version of Hiram Berdan to organize their sharpshooters. Major General Patrick Cleburne, who had served in Arkansas with the Yell Rifles, organized battalions in the South using Whitworth, Kerr and Enfield rifles.

Beyond scopes and rifles, sharpshooters used other specialized equipment. There were tree-climbing spurs for their boots similar to what electric utility workers use today. There were portable range-finding instruments. Shooting glasses obscured all but the eyepieces of the scopes, and keyhole-shaped inserts for the scopes themselves occluded everything but the outline of the human form.

The Union Army initially dressed sharpshooters in green felt uniforms as a form of camouflage until discovering that their distinctive dress made them targets of Confederate sharpshooters. Brass buttons were replaced with black rubber ones that did not reflect the light. Hollow bullets filled with explosive ampoules of fulminate of mercury were also used.

Special tactics included splashing sand into the mouths of cannons to rupture the guns upon firing, and killing mounts and draft animals to hamper the enemy’s mobility. The specific targeting of officers was an obvious tactic which was described in social as well as military terms.

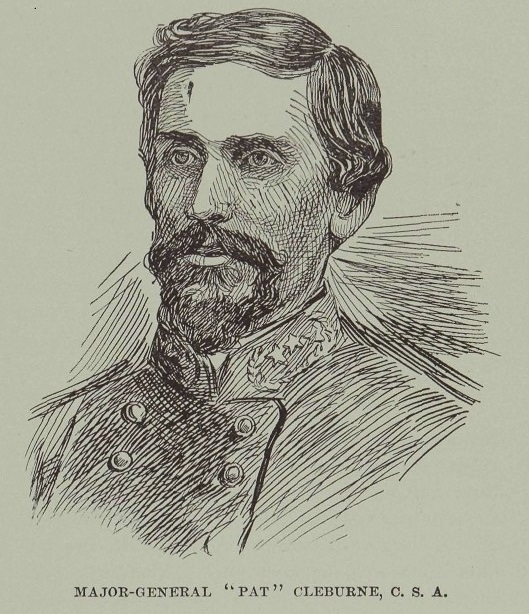

Why we Lose so Many Officers. “Hermes,” writing to the Charleston Mercury from Richmond, alluding to the battle of Gen. Jackson near Winchester, says:

It will be noticed that in this battle, as at Elkhorn, in Arkansas, and other recent actions, our losses in officers have been grievous. To account for this by the real or supposed rashness of the officers themselves, will not answer. It will be found, sooner or later, that the Yankees have organized in each army a band of practiced sharp-shooters, whose business it is, with long range rifles, to pick off the officers. By means of telescopic sights, this can be done at a great distance, and where the sharp-shooter himself is entirely out of danger. All he has to do is to put his rifle at rest, adjust his telescope, and shoot down officer after officer. The design in this murderous business is obvious. The Yankee theory is that the rebellion is due to men of influence, by whose pernicious example the ignorant are led astray from the fold of the “glorious Union.” Destroy the leaders and the rest become like lost sheep.

The most telling murder of a leader, however, came at the hands of Confederate sympathizers through the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. And it turns out that the telescopic rifle was mentioned as a possible means of doing so. In the 1867 trial of conspirator John Surrat, a woman testified to overhearing David Herold and George Atzerodt mention the words “telescope rifle” in conjunction with Lincoln’s name while conversing on a street corner in Washington, D.C. in 1864. She then watched as the pair was joined by John Wilkes Booth.

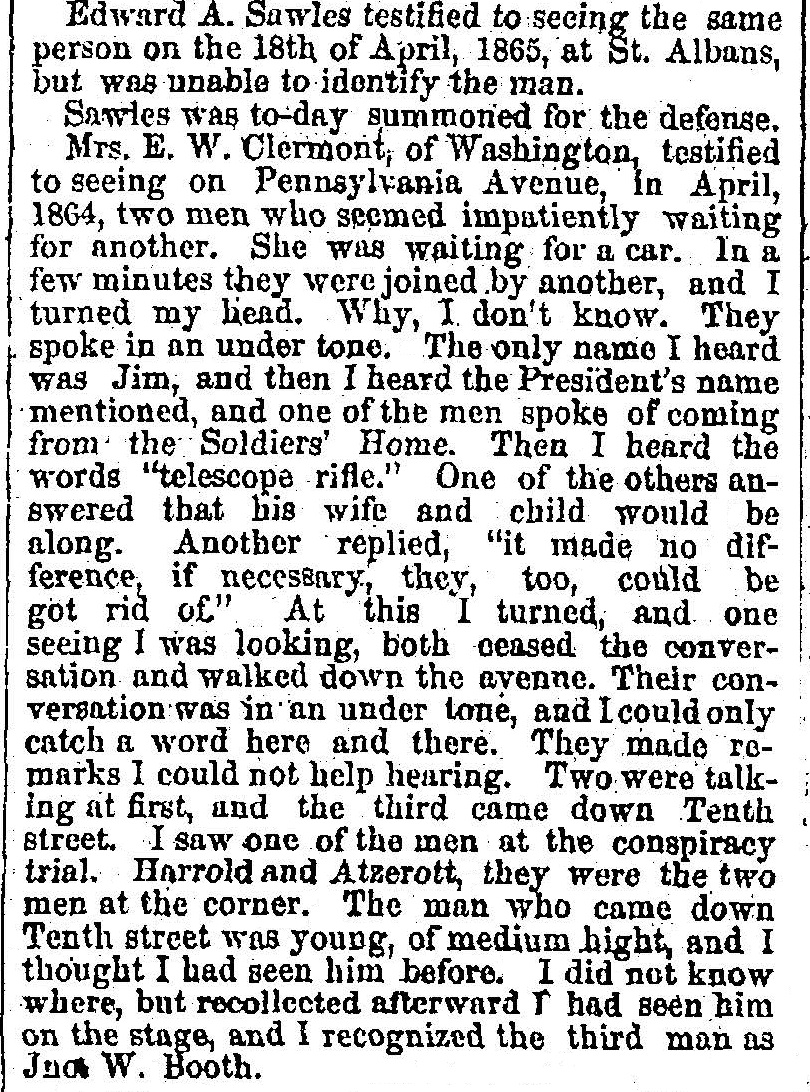

Mrs. E.W. Clermont, of Washington, testified to seeing on Pennsylvania Avenue, in April, 1864, two men who seemed impatiently waiting for another. She was waiting for a car. In a few minutes they were joined by another, and I turned my head. Why, I don’t know. They spoke in an under tone. The only name I heard was Jim, and then I heard the President’s name mentioned, and one of the men spoke of coming from the Soldiers’ Home. Then I heard the words “telescope rifle.” One of the others answered that his wife and child would be along. Another replied, “it made no difference, if necessary, they, too, could be got rid of.” At this I turned, and one seeing I was looking, both ceased the conversation and walked down the avenue. Their conversation was in an under tone, and I could only catch a word here and there. They made remarks I could not help hearing. Two were talking at first, and the third came down Tenth street. I saw one of the men at the conspiracy trial. Harrold and Atzerott, they were the two men at the corner. The man who came down Tenth street was young, of medium hight [sic], and I thought I had seen him before. I did not know where, but recollected afterward I had seen him on the stage, and I recognized the third man as Jno. W. Booth.

History would have been markedly different had President Lincoln been shot from hundreds of yards away by a disaffected Confederate marksman or a trained co-conspirator. Witnesses would have been few if any, and Booth would not have injured his leg during his escape. Similar measures could have been exerted against Vice President Andrew Johnson, Secretary William H. Seward, and many others resulting in a full-scale coup d’état.

It was certainly possible and apparently contemplated to assassinate Lincoln using a telescopic rifle, but even the scope’s magnification would not have done justice to that president who already loomed large in the nation’s consciousness and destiny. Telescopic sights have since given way to night vision technology and drone warfare. What remains is the casus belli, the impetus for war, and the higher power to which men appeal in their pursuit of victory.