Freedom by Express: The Life and Daring Escape of Henry Box Brown

Henry Brown was born into slavery, circa 1815, 45 miles outside of Richmond, Virginia. As a young man, he was taken to work in the Richmond tobacco factory of his owner, William Barret. Well-regarded by Barret, Brown was generally treated kindly, but soon grew acutely aware of the cruelties visited on his fellow slaves.

Brown fell in love with a slave woman named Nancy who was owned by a local banker. Both owners consented to the marriage. Although Nancy’s owner pledged to never sell Brown’s wife and break up the family, she was sold twice during their marriage. Nancy’s third owner, Samuel Cottrell, extorted Brown, requiring him to pay $50 a year to prevent the sale of Nancy and their three children.

One evening in August 1848, Brown returned home to find his wife and children gone. Cottrell had sold them, and they were being held in the local jail awaiting transport to North Carolina. As his family was taken from Richmond, Brown followed, holding his wife’s hand for four miles. He never saw Nancy or his children again.

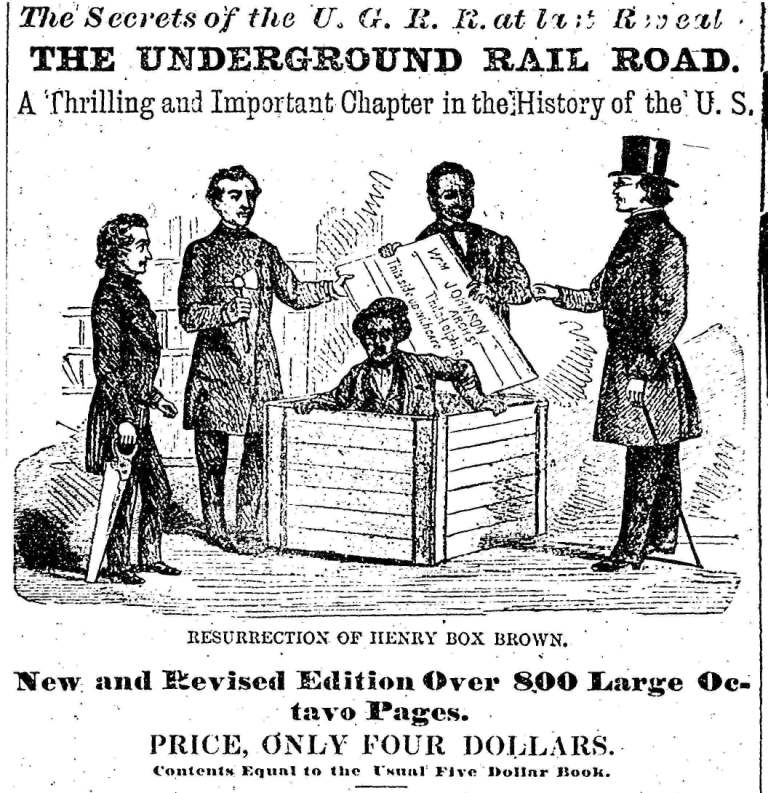

The loss of his family devastated Henry Brown, but it also steeled his resolve to escape slavery. Looking for a way to reach the northern states, Brown came upon the idea of shipping himself in a box. He found help from two men: James C. A. Smith, a free African American who was a member of Brown’s church, and Samuel Smith, a white merchant who agreed to assist Brown in exchange for $86. On March 23, 1849, Brown was nailed into a crate 2-feet wide, 3-feet long and 2 ½-feet deep. Three holes in the wood allowed him to breathe, while a small bladder of water and some biscuits were his only provisions. The box was labeled “dry goods” and addressed to James Miller McKim, a leader of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. Brown’s journey had begun.

Brown remained in the box for 27 hours, traveling a distance of 350 miles. Through determination, he was able to remain silent and undetected for the entire trip. Although the box was clearly marked to keep right side up, Brown was turned upside-down and spent several very painful hours on his head. Blood rushed to his eyes and he feared he would die, but he endured. Finally, Brown’s box was delivered to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. After ascertaining that Brown was still alive, they quickly opened the crate. Although weak from his journey, Brown broke into song, singing Psalm 40: “I waited patiently for the Lord, and He inclined to me and heard my cry.”

Brown became a sensation in the northern press and among abolitionists. He changed his name to Henry Box Brown and gave lectures detailing his escape from slavery. He soon incorporated a large panorama painting of slave life into his show, entitled “Mirror of Slavery.” Although Brown was illiterate, a written account of his life story, Narrative of Henry Box Brown who Escaped from Slavery Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide Written from a Statement of Facts Made by Himself. With Remarks upon the Remedy for Slavery. By Charles Stearns, was published in 1849. Although it told Brown’s story, it was as much devoted to its author’s views on slavery as to Brown’s tale of escape.

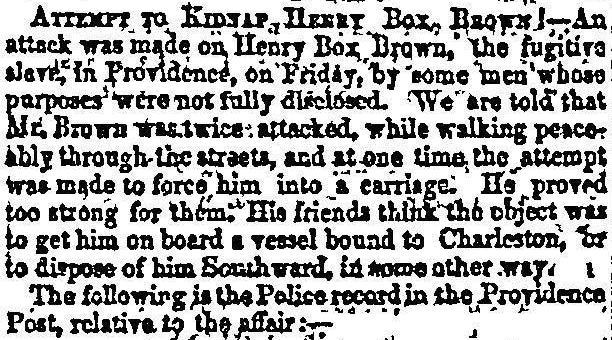

Henry Box Brown enjoyed his freedom and new-found celebrity, but it was not to last. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act meant that escaped slaves like him could be captured and returned to their owners in the south. After Brown was accosted in Providence, Rhode Island, he though it wise to leave America and head to the safety of Great Britain.

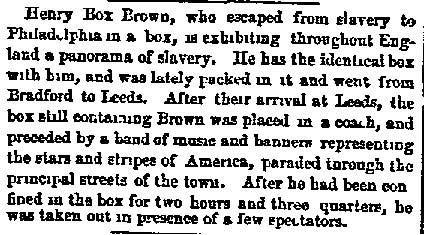

Accompanied by his friend James C. A. Smith, Brown soon established himself in Britain as a foremost abolitionist lecturer and entertainer. In 1851, Brown released a second version of his biography, Narrative of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself. Free of Charles Stearns’ heavy prose and moralizing, the second work conveys Brown’s life and point of view much more clearly. While in Britain, Brown excelled as a showman, reenacting his great escape by mailing himself from the town of Bradford to Leeds.

Although free from slavery in Britain, Brown was not free of trouble. He and James Smith quarreled over money and soon dissolved their partnership. Smith criticized Brown for taking an English wife instead of trying to find and purchase Nancy. Other abolitionists criticized his showmanship and ostentatious dress. The harshest criticism came from respected abolitionist and escaped slave Fredrick Douglass. Douglass contended that since Brown had publicized his means of escape, no other slaves could ever repeat his method to gain their own freedom. (Indeed, Samuel Smith, the merchant who aided Brown, had attempted to ship two other slaves to freedom shortly after Brown’s success. Smith was captured and sentenced to six and a half years in prison.)

As the years passed, Brown began to abandon abolitionist causes and focus more on show business. Although he continued to show his famous box and his slavery panorama, he also began showing panoramas of other historic events. He dabbled in stage magic and hypnotism, styling himself at various times as Professor H. Box Brown and “King of the Mesmerisers.” Brown and his British wife had a daughter Annie. He returned to the U.S. in 1875, and promoted his magic shows through advertisements and handbills. The last known mention of Henry Box Brown is for a performance in Bratford, Ontario, Canada, on February 26, 1889. Brown disappears after that, and the exact date, location, and cause of his death are unknown.

Although few facts about his life are known, Henry Box Brown and his story endure. The innovation of his escape, the courage and determination he showed during his confinement in the box, captivated audiences during his lifetime. Scholars have debated the meaning of his story and its symbolism. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., posited that Brown’s daring escape symbolized death while in slavery and rebirth in freedom. It is surely no coincidence that the famous print of Brown emerging from his box is titled The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown in Philadelphia. Brown is also symbolic for what he did after his escape. He used his showmanship to create a new identity for himself, quite apart from the role abolitionists would have created for him. Brown was his own man, and no one else’s.

Bibliography:

Brooks, Daphne A. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Ernest, John. Appendix to Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself.123-175. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Gates, Henry Louis. Forward to Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself. vi-x. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Spencer, Suzette. Encyclopedia Virginia. “Henry Box Brown (1815 or 1816-after February 26, 1889.)” Accessed January 29, 2013. http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/brown_henry_box_ca_1815