The Early Histories of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Part III: Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute

Booker Taliaferro Washington was born April 5, 1856 in Virginia the son of an enslaved woman named Jane who later, after emancipation, was able to reunite with her husband, Washington Ferguson, in West Virginia. Booker’s father is unknown. He may have been a white man. Washington never knew when he was born. Nevertheless, he was a slave until he was nine years old when the U.S. Army occupying troops began to enforce emancipation.

When they arrived in West Virginia, young Booker attended school for the first time and learned to read. He was an apt student who rapidly acquired knowledge and skills. He did hard labor to earn money in order to attend the Hampton Institute and later a seminary in Washington, D.C. At the age of 25 he was selected to be the first head of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute [Tuskegee University] which opened July 4, 1881.

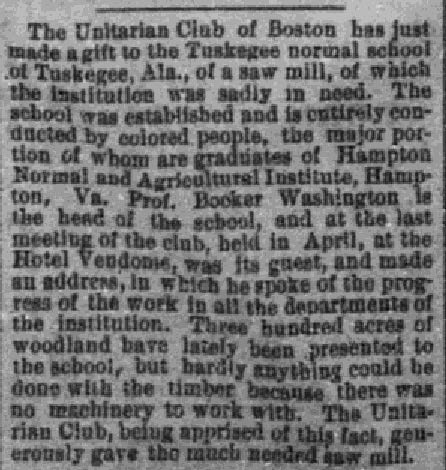

In a few short years Washington began emerging as one of the most influential voices on behalf of the education and skills acquisition necessary for former enslaved people and their descendants. An early article in the press concerning his endeavors was published on June 28, 1886 in the Worcester Daily Spy of Massachusetts.

The Unitarian Club of Boston has just made a gift to the Tuskegee normal school of Tuskegee, Ala., of a saw mill, of which the Institution was sadly in need.

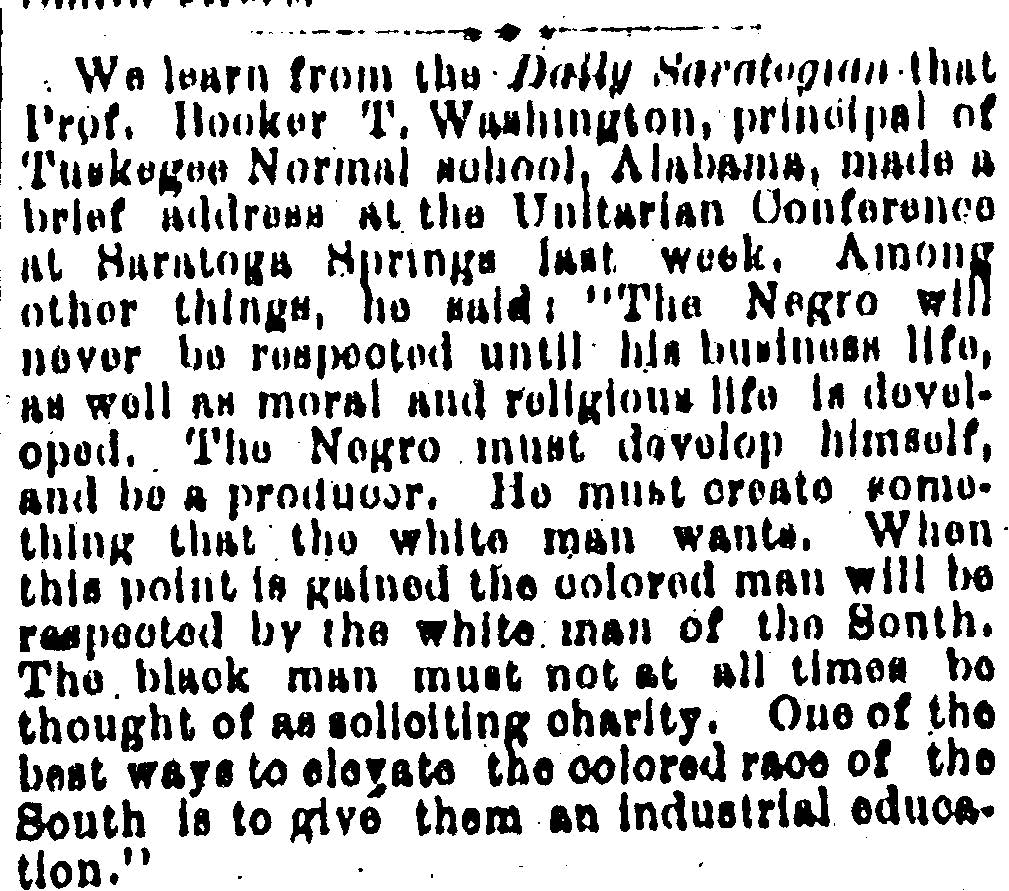

In September of that year, Washington spoke at the Unitarian Conference as reported by The New York Freeman on October 2nd.

We learn from the Daily Saratogian [sic] that Prof. Booker T. Washington, principal of the Tuskegee Normal School, Alabama, made a brief address at the Unitarian Conference at Saratoga Springs last week. Among other things, he said; ‘The Negro will never be respected until his business life, as well as moral and religious life is developed. The Negro must develop himself, and be a producer. He must create something that the white man wants. When this point is gained the colored man will be respected by the white man of the South. The black man must not at all times be thought of as soliciting charity. One of the best ways to elevate the colored race of the South is to give him an industrial education.’

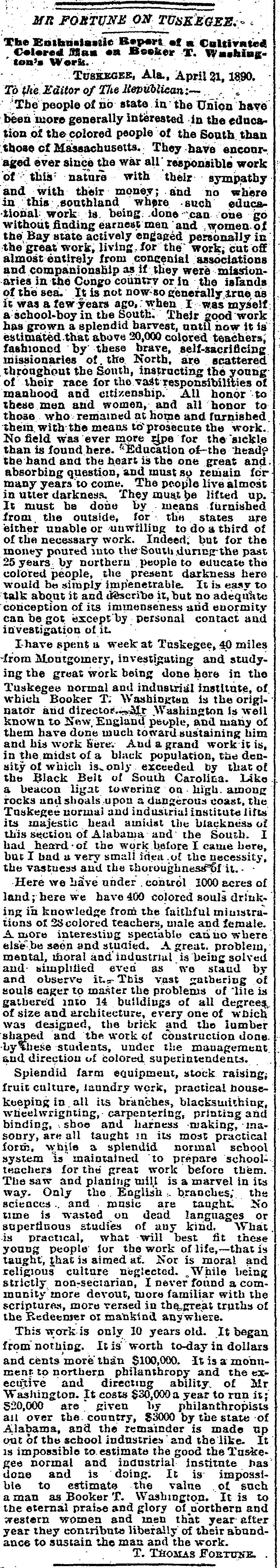

This was his succinct expression of his abiding philosophy. He did not disregard the value of academic education and encouraged it, but he remained adamant throughout his life that black people must produce something tangible and desired to gain acceptance. He worked diligently to accomplish this mission. By 1890 the Institute was thriving, as recounted in a letter to the editor of the Springfield Republican in Massachusetts from a recent visitor to Tuskegee on April 21, 1890.

Here we have under control 1000 acres of land, here we have 400 colored souls drinking in knowledge from the faithful ministrations of 28 colored teachers, male and female. A more interesting spectacle can no where else be seen and studied. A great problem, mental, moral and industrial is being solved and simplified even as we stand by and observe it… Splendid farm equipment, stock raising, fruit culture, laundry work, practical housekeeping in all its branches, blacksmithing, wheelwrighting, carpentering, printing and binding, shoe and harness making, masonry, are all taught in its most practical form, while a splendid normal school is maintained to prepare schoolteachers for the great work before them.

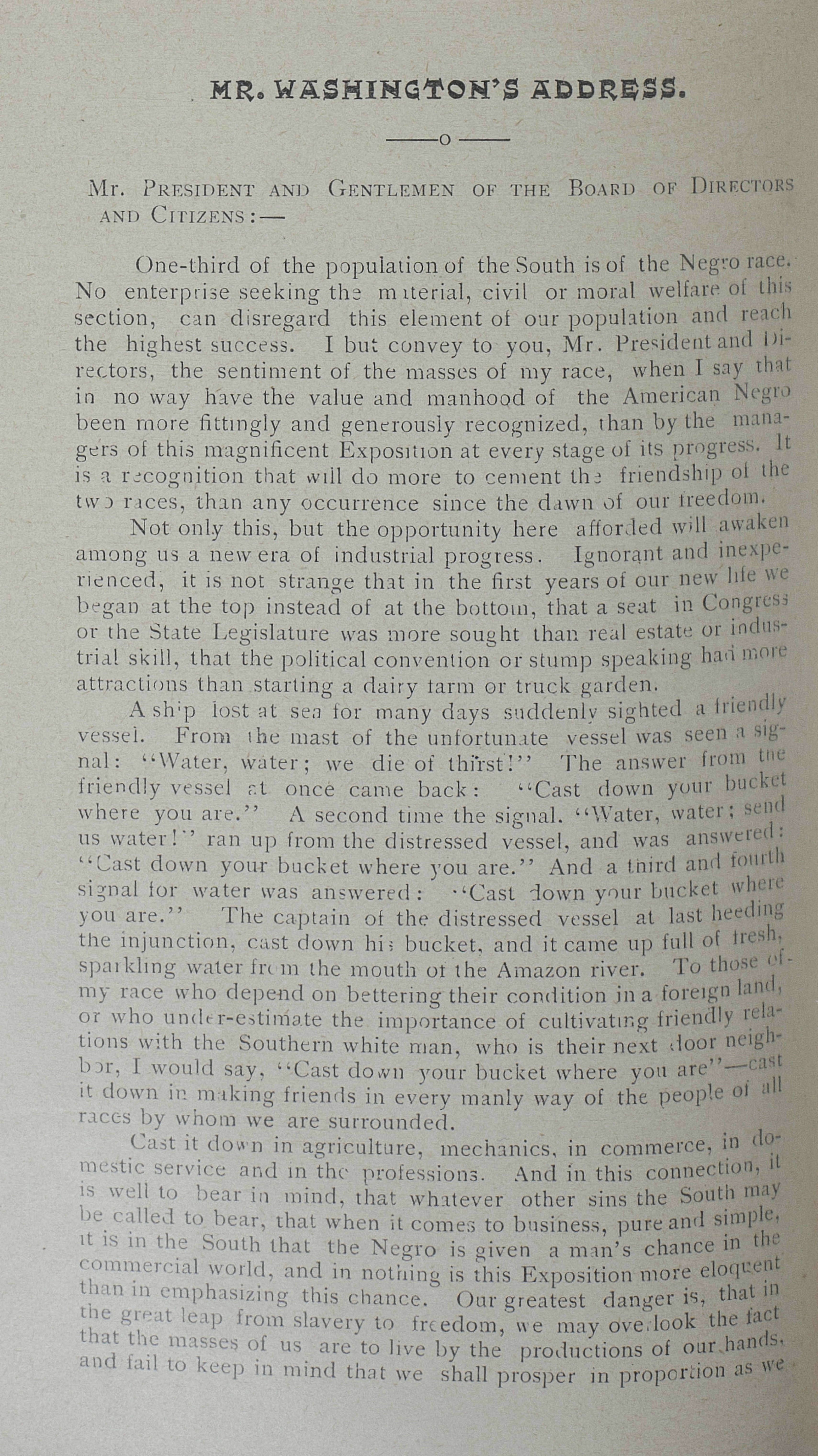

On September 18, 1895, Washington gave an address to the Cotton States and International Exposition which is considered to be one of the most consequential speeches in our history. He announced the Atlanta Compromise, an unwritten but far-reaching agreement that African Americans would not seek the vote or higher education, would accept segregation and discrimination in return for being provided free education limited to industrial and vocation pursuits. The Compromise was initially accepted by W.E.B. Du Bois, who was emerging as a rival voice to Washington’s. This would change.

Clark Howell, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, gave fulsome praise to the speech and the concept in a signed article published by the New York World on September 19th.

I do not exaggerate when I say that Prof. Booker T. Washington’s address yesterday was one of the most notable speeches, both as to character and the warmth of its reception, ever delivered to a Southern audience. It was an epoch-making talk, and marks distinctly a turning point in the progress of the Negro race, and its effect in bringing about a perfect understanding between the whites and blacks of the South, will be immediate. It was the first time that a Negro orator had appeared on a similar occasion before a Southern audience.

The speech is a full vindication from the mouth of a representative Negro of the doctrine so eloquently advanced by Grady and those who have agreed with him that it is to the South that the Negro must turn for his best friend, and that his welfare is so closely identified with the progress of the white people of the South, that each race is mutually dependent upon the other, and that the so-called ‘race problem’ must be solved in the development of the natural relations growing out of the association between whites and blacks of the South.

The speech resonated across the country and elevated Washington to a position of national prominence. The Omaha World-Herald reprinted an article from the Chicago Times-Herald on October 7, 1895 under the headline “Moses of the Colored Race.”

Since the death of Fred Douglass the colored people of America have had no one generally recognized as a type of what the emancipated negro might become until at the opening of the Atlanta exposition the best speech of the day was made by Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute, a speech which at once caused him to be known to the many, as he was already known to the few, as the wisest and truest leader of his race this country has ever produced. And not only of his own race, for he ranks with the most skillful of white educational organizers of the highest executive capacity, of cultural prudence, and judgment, devotion and missionary enthusiasm.

The article quotes General Samuel Armstrong, the founder of the Hampton Institute--a school dedicated to the practical, industrial education of young African Americans--who when asked if the Institute had been successful in its mission, responded:

If I had done nothing else here worthy of praise, I should feel that my long devotion to the undertaking had been repaid in the training and commissioning of so remarkably useful man as Booker T. Washington.

The article is lengthy and merits attention for its lavish praise and what may seem to contemporary readers as condescension, if not racism, in such statements as:

They [blacks] are still large, muscular, with broad chess, capable of wrestling fortunes out of the fertile soil of Alabama. They have common sense, wit and capacity for thoughtfulness quite equal to the white peasantry of Europe.

Not everyone was happy with the speech. The Washington Bee, a black-owned newspaper, reported about a meeting of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society under the headline “Booker T. Washington Denounced.” The article appeared on October 26, 1895.

Addresses were also made by… Mr. L.W. Pulies and Mr. Wetherless. The two last speakers carried the house by storm.

Whetherless in his remarks declared the speech hypocritical and showing the natural bent of the man, for instance that within a few squares of Tuskegee Institute, Prof. Booker T. Washington’s college a negro dared to entertain as his guest a white Northern gentleman.

For this crime (?) a negro was mobbed and grievously injured. He was taken to Tuskegee Institute for medical aid, and Mr. Washington, the negro of a negro institute refused a fellow negro admittance to his negro college, thereby denying the right of medical assistance… The house roared at these remarks.

Mr. Pulies added:

But I deny as alleged and claimed that his was the greatest negro speech ever delivered by any negro in the United States. That his speech was one which conceded the inferiority of the negro; it ignored the civil rights of the negro, but conceded just treatment. If accepted as the greatest speech ever delivered by a negro, then it was a standing rebuke to the sturdy manhood; the eloquent protest against outrage and the life work of the immortal Frederick Douglass, and a refutation of the exposures of barbarism and wholesale murder of negroes, echoed through two continents by Ida B. Wells.

The negro in this whole affair is merely a catspaw for the Atlanta Exposition.

The Washington Bee continued its criticisms as exemplified by a brief but terse article on April 11, 1896.

Mr. Booker T. Washington is an apologist pure and simple and those who indorse his schemes are no better than he.

Whether or not Washington was an apologist, it is clear that he was an incrementalist; he was willing to wait for justice as long as he was able to elevate his race according to his convictions. In a speech at Harvard, as reported by the Enterprise of Omaha, Washington said:

We are to be tested in our patience, our forbearance, our perseverance, our power to endure wrong, to withstand temptations, to economize, to acquire and use skill. Our ability to compete, to succeed in commerce, to disregard the superficial for the real, the appearance for the substance, to be great and yet small, learned and yet simple, high and yet the servant of all. This, this is the passport to all that is best I the life of our Republic, and the Negro must possess it, or be disbarred.

The speech was widely lauded, but not in all quarters. The Washington Bee remained critical of his mission as reported on December 12, 1896. The article is brief and wounding.

The editor of the Age is of the opinion that we not understand Mr. Booker T. Washington. Oh! yes. He is a money-making machine for the Tuskegee Institute and an Afro American apologist.

In a few years W.E.B. Du Bois would emerge as new voice for the race, a voice much less patient than Washington’s. For the first 15 years of the 20th century these two inestimable men would have a powerful influence on the progress of a disenfranchised people toward a fuller participation in society.

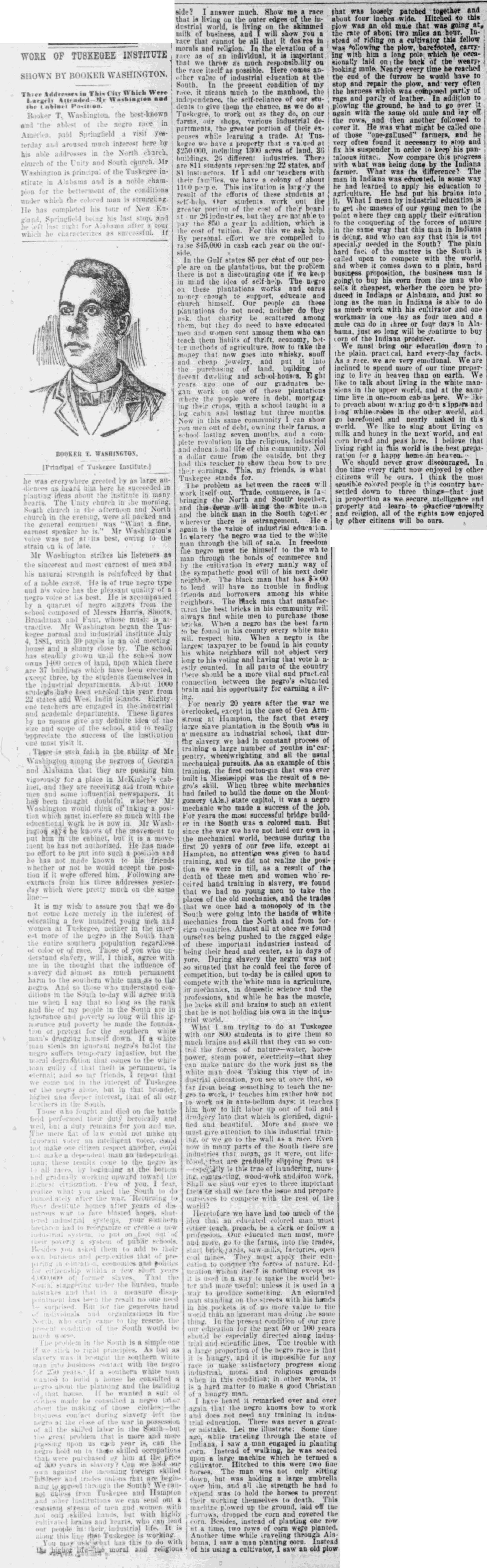

Throughout his life Washington never wavered. Certainly, he was constant in his efforts to raise money for the Tuskegee Institute. Much in the way the Jubilee Singers built Fisk University by the money they earned on concert tours, so he raised money for Tuskegee by giving speeches on tour. In this manner and in the success of the students, Washington built a solid foundation on which a great university flourished. The Springfield Republican in Massachusetts was a consistent supporter of his efforts as is reflected in an article published on December 21, 1896.

Booker T. Washington, the best-known and ‘the ablest of the negro race in America, paid Springfield a visit yesterday and aroused much interest here by his able addresses in the North church, church of Unity and South church. Mr. Washington is principal of the Tuskegee institute in Alabama and is a noble champion for the betterment of the conditions under which the colored man is struggling… [he] strikes his listeners as the sincerest and most earnest of men and his natural strength is reinforced by that of a noble cause.

The article is a fair representation of Washington’s philosophy as summed up in the last two paragraphs.

We must bring our education down to the plain, practical, hard every-day facts. As a race we are very emotional. We are inclined to spend more of our time preparing to live in heaven than on earth. We like to talk about living in the white mansions in the upper world, and at the same time live in one-room cabins here. We like to preach about wearing golden slippers and long white robes in the other world, and go barefooted and nearly naked in this world. We like to sing about living on milk and honey in the next world, and eat corn bread and peas here. I believe that living right in this world is the best preparation for a happy home in heaven.

We should never grow discouraged. In due time every right now enjoyed by other citizens will be ours. I think the most sensible colored people in this country have settled down to three things – that just in proportion as we secure intelligence and property and learn to practice morality and religion, all of the rights now enjoyed by other citizens will be ours.

The final blog in this series about HBCUs will explore the work of W.E.B. Du Bois and how he and Washington clashed in their views while sharing the same goal.