“Expanding human control over nature:” How the CIA created a record for understanding the controversy over genetic engineering

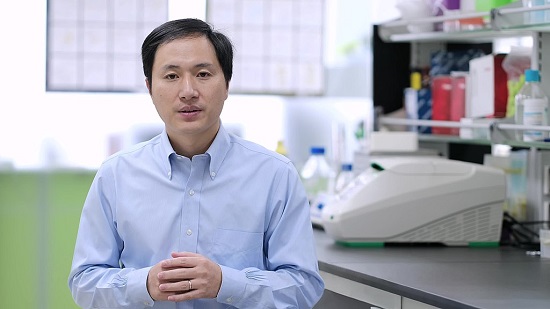

In 2018, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui secretly altered the DNA of a pair of human embryos to make them resistant to the HIV virus. When the twin babies were born and Dr. He announced what he’d done, scientists and governments around the world condemned him. One researcher called his actions “unconscionable...an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible.” The Chinese government launched an investigation, and media circulated calls to ban or limit the technology that made the genetic engineering possible.

The CIA, no doubt, was paying attention to the whole hoopla. Although the twin babies represent the current apogee of genetic engineering, Dr. He’s work was predicated on decades of research and debate—much of which was monitored by the CIA, which has experimented with using genetically-engineered insects and other animals as instruments of espionage.

From the 1950s to the mid-1990s, a division of the CIA recorded and translated into English publications and media from around the world that covered bioethical issues, including genetic engineering. Today, as our ability to edit an organism’s genetic makeup grows increasingly powerful—and contentious—researchers in numerous disciplines are searching these primary source documents for a record of the technical advances and ethical discussions that led to this watershed moment.

Morality and Science: Global Origins of Modern Bioethics, 1957-1995, begins just as researchers were figuring out how to manipulate the genes of bacteria and other simple organisms. “What is already possible to a modest degree among viruses and bacteria…can be expected for the higher organisms (including man) at the turn of the millennium,” wrote Rolf Loether in East Berlin’s Sozialistische Einheit newspaper in 1970. “This signifies a crucial expansion of human control over nature.”

In some cases, this “control over nature” was met with unambiguous support. Such was the case in the 1980s, when the FDA approved the use of a drug produced by bacteria genetically engineered to synthesize human insulin. A report in Budapest’s Nepszabadsag newspaper described the nitty-gritty of what this work looked like: “A little petri dish in which there was a sort of green material.” The petri dish “did not say much to the uninitiated,” but to the “several hundred experts sitting in the large lecture hall of the Szeged Biological Center,” its contents held the potential to revolutionize medical care and quality of life for diabetics.

Other advances also promised to transform human life. Creators of corn and other crops engineered to resist insects and herbicides, for instance, believed their work would help farmers grow enough food to feed the world’s burgeoning population. But as scientists moved beyond bacteria and began fiddling with the genes of plants and animals, some observers worried about unintended consequences.

“In view of our almost total ignorance of vast areas of biology, it is evident that we will often lack the necessary information for deciding whether it is safe to make a new organism,” Bill Wilson, a professor of cell biology at New Zealand’s Auckland University, told the Wellington Evening Post in 1977.

When the chemical company Monsanto began selling seeds for herbicide-resistant soybeans in the 1990s, for example, farmers suddenly had free rein to spray prodigious amounts of herbicides. That led to die-offs of unwanted native plants like milkweed, which in turn contributed to worldwide declines of monarch butterflies and other beneficial insects.

And because genetic engineering was expensive work, university and government researchers were often hamstrung by lack of funding, which meant Monsanto and other petrochemical giants funded much of the research. “Our laboratory…can only continue thanks to the support we receive from industry,” plant geneticist Marc Van Montague told Paris’ Biofutur in 1985. “Dow Chemical, Du Pont, and Monsanto are all off to a good start in this field.”

Industry-funded science, however, is often driven less by public good than by economic interests, which led to further concerns about genetic engineering. In 1990, Germany became the first country to establish rules governing how private companies could use this powerful new tool. The new law was “intended to protect human, animal and plant life and the entire environment as regards its entire constitution and material assets from potential dangers inherent in genetic engineering processes and products,” reported MPG Spiegel in 1991.

Today, some observers believe that concerns over the perils of genetic engineering have swung too far, leading to unfounded paranoia and the kind of overly-stringent regulations that drive researchers like He Jiankui underground, where they operate with even less oversight. When that happens, it also limits the ways that genetic engineering can benefit humankind—through insulin-producing bacteria, say, or other organisms whose potential has yet to be uncovered.

As researchers and regulators navigate these ethically murky waters, the CIA’s archive—now available digitally through Readex’s Morality and Science: Global Origins of Modern Bioethics—may offer a way forward, by illuminating the mistakes and lessons of the past.