"We are in the midst of the most terrible battle of the war—perhaps history." 1 So wrote General George McClellan to Chief of Staff Henry Halleck and President Abraham Lincoln before the telegraph wires went dead the morning of September 17, 1862. The wires would remain dead all day, as the battle of Antietam consumed the lives of 6,000 men and the fate of the nation lay in the balance.

Indeed, the first report of Antietam's outcome to reach Lincoln would come not from his generals, but from a reporter, George Smalley of the New York Tribune. Smalley had guessed where the two massive armies would converge, and was there from the beginning, joining General Hooker on horseback. During a crisis early in the battle, Hooker's attention was drawn to Smalley, who was gazing at the battle around him with cool aplomb. "In all the experience which I have had of war," Hooker would later write, "I never saw the most experienced and veteran soldier exhibit more tranquil fortitude and unshaken valor than was exhibited by that young man." 2

Early in the fighting Hooker turned to Smalley and enlisted him as his official messenger to his officers, which put Smalley in one of the most dangerous and important roles on the battlefield. Smalley had two horses shot out from under him, but lived to not only deliver Hooker's orders but to observe the entire battle so keenly that his published report in the Tribune came to be known as the standard against which all battlefield reporting would be measured.

That Smalley managed to do this at all is surprising enough, but that he did it so well almost defies belief. A sample:

The battle began at dawn. Morning found both armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each others eyes. The left of Meade's reserves and right of Rickett's line became engaged at nearly the same moment, one with artillery, the other with infantry. A battery was almost immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a ploughed field near the top of the slope where the cornfield began. On this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods which stretched forward into the broad fields like a promontory into the ocean, were the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day.

For half an hour after the battle had grown to its full strength, the line of fire swayed neither way. Hooker's men were full up to their work. They saw their General everywhere in front, never away from the line, and all the troops believed in their commander, and fought with a will. Two thirds of them were the same men who under McDowell had broken at Manassas.

Many detailed columns later, he continues:

"The fight in the ravine was in full progress, the batteries in the center were firing with renewed vigor, Franklin was blazing away on the right, and every hilltop, ridge and woods along the whole line was crested and veiled with white clouds of smoke. All day had been clear and bright since the early cloudy morning, and now this whole magnificent scene shone with the splendor of an afternoon September sun. Four miles of battle, its glory all visible, its horrors all hidden, the fate of the Republic hanging on the hour—could anyone be insensible of its grandeur?"

And then finally:

The field and its ghastly harvest which the Reaper had gathered in those fatal hours remained finally with us. Four times it had been lost and won. The dead are strewn so thickly that as you ride over it you cannot guide your horse's steps too carefully. Pale and bloody faces are everywhere upturned. They are sad and terrible, but there is nothing which makes one's heart beat so quickly as the imploring look of sorely wounded men who beckon wearily for help which you cannot stay to give. 3

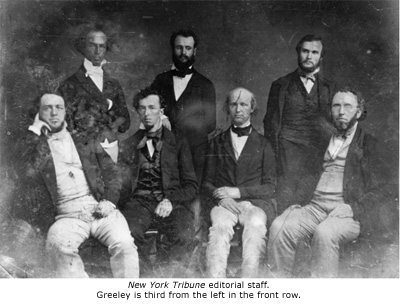

That men of Smalley's caliber worked for the New York Tribune was not a matter of chance. Of the roughly 150 Northern correspondents covering the Civil War, more than half were from two papers alone, the New York Tribune and the New York Herald. 4 There were many other good papers covering the war from the front line—notably the Philadelphia Inquirer in the North, and the New Orleans Picayune and several Richmond dailies in the South—but only the Tribune and the Herald had the money and the will to cover the war in such depth.

The publishers of these papers, Horace Greeley of the Tribune and James Gordon Bennett of the Herald, had perfected a new form of journalism in the 1830s and 40s—the "Penny Daily"—and had amassed fortunes in the process. They were journalists to the bone, reporters at heart, and when the war came they were ready to cover it like no war had been covered before.

The government and the military were ready to comply. "Probably no great war has ever been so thoroughly covered by eye-witness correspondents as the American Civil War," writes Frank Luther Mott in his monumental "American Journalism." "Newspapers have printed far greater volumes of material about later wars…but Civil War conditions allowed for more uncensored, on-the-scene reporting." 5

Indeed, Smalley's pivotal role in the military action at Antietam was not unusual. B.S. Osbon, a reporter for the Herald, acted as Admiral Farragut's signal officer and won the highest praise of the Admiral for saving the life of his commanding officer and the ship itself.

Albert D. Richardson of the Tribune was also aboard a Union war-ship when disaster struck at Vicksburg. Attempting to run a blockade there, his ship was strafed by cannon-fire and exploded, hurling Richardson overboard and finally into a Confederate prison. Eventually he escaped and traveled slowly North 400 miles on foot, mostly by night, on the "Underground Railroad." His detailed and harrowing account of the entire adventure appeared in the Tribune, proclaiming (with a nod to Tennyson): "Out of the Jaws of Death! Out of the Mouth of Hell!" 6

These reports—widely reprinted in both North and South—electrified the nation and cemented the already towering reputations of Bennett and Greeley. Indeed, the stories of these two men themselves are equally full of perseverance, ingenuity and courage.

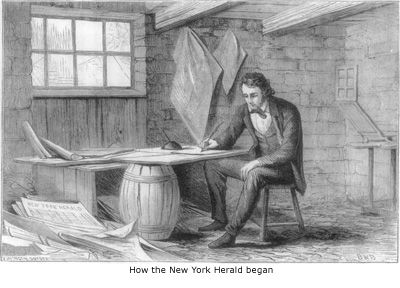

Bennett had started the Herald in 1835 as a one-man show down near Wall Street, where he did all the reporting, all the writing and all the editing himself, the latter on a pine board thrown over the tops of two flour barrels. Mind you, this was a daily newspaper.

Greeley, a poor farm boy from New Hampshire, founded the Tribune in 1841. Between the two of them, he and Bennett practically invented the newspaper as we know it today, creating such novelties as stock market reports, police blotters, society and sports columns, human interest stories and sections devoted to poetry and literature. Along the way, they founded the Associated Press, built high-speed steam-ships to intercept incoming news from Europe halfway across the Atlantic and amassed the fortunes it would take to cover the coming war not only with in-depth on-the-scene narratives but with detailed illustrations of aerial maps and battle scenes.

Their coverage of the Civil War and the political stances they took often put the publishers themselves in harm's way. Greeley took a radical Republican stance during the war, opposing Lincoln's more moderate positions, and this stance among others so enraged his readers that at one point a mob attacked the Tribune building and set it ablaze. Greeley immediately rebuilt and continued publishing under constant guard by the police. By the end of the war, the Tribune and the Herald had the largest circulations in the world.

America's Historical Newspapers will include all of the Civil War coverage of these two papers, along with that of more than 100 other newspapers that covered the War, including the Philadelphia Inquirer, the New Orleans Picayune and the important Richmond papers. It is our hope that by bringing this massive assemblage of on-the-scene Civil War reporting to an ever-wider audience in a format that enables instant searching and comparison, we are in our own small way supporting the original goals of Greeley and Bennett: Get the story out, at all costs.

References

1 Brew, Cowan, "George Smalley: Reporting from Battle of Antietam," 1, Reprinted online.

2 "Wilkes' Spirit of the Times", VII (February 7, 1863), 360 Cited in: Andrews, J. Cutler, The North Reports the Civil War, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985), 277

3 Brew, Cowan, "George Smalley: Reporting from Battle of Antietam," 1-3, Reprinted online.

As transcribed from the New York Herald

4 Mott, Frank Luther, American Journalism, A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 years 1690-1940, (New York: Macmillan, 1947) 332, and Andrews, J. Cutler, The North Reports the Civil War, (Pittssburth: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985) 20

5 Mott, Frank Luther, American Journalism, A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 years 1690-1940, (New York: Macmillan, 1947) 329

6 Ibid, 335