“An Engine of the Most Diabolical Oppression”: Highlights from the American Slavery Collection

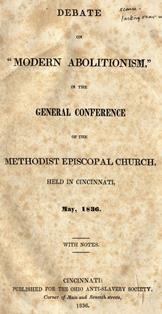

Debate on "Modern Abolitionism," in the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, held in Cincinnati, May, 1836 (1836)

In response to “the unjustifiable conduct of two members of the General Conference,” anti-abolitionist delegates of the 1836 meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church supported two resolutions. In the first, they disapproved “in the most unqualified sense” of “the conduct of the two members…who are reported to have lectured…upon, and in favor of, modern abolitionism.” With the second resolution, they “decidedly” opposed “modern abolitionism, and wholly disclaim[ed] any right, wish or intention, to interfere in the civil and political relation between master and slave, as it exists in the slaveholding states of this Union.”

Delegate Paine, of Alabama, spoke of the overall population’s opposition to abolition, even in the free state of Ohio, asking:

What would be the consequence, if an abolition meeting were now advertised to be held at the Court-House in this City? If such a thing were projected…you would see the indignant crowd, gathering in the streets, and presenting a dark and dense mass, making its way to the appointed place, to pour out its vengeance on those, who might be rash enough to engage in such a scheme.

It would seem…that nothing can cure them, [the abolitionists,] – they stop at nothing – still they persist, notwithstanding the impediments, which they are continually encountering in popular hatred and persecutions. They persevere in aggravating the slave-holder – using against him reproachful terms – injurious epithets. Not satisfied with the extent of their operations in the North, they are here, in the West…

Speech of Mr. Cushing of Massachusetts, on the Proposition to Censure Mr. John Quincy Adams, for an Alleged Disrespect to the House of Representatives (1837)

By Caleb Cushing

Anti-abolitionist sentiment was also strong within the House of Representatives of the Twenty-fourth United States Congress. So strong that the House adopted the following resolution on January 18, 1837:

Resolved, That all petitions memorials, resolutions, propositions, or papers relating in any way, or to any extent whatever, to the subject of slavery, or to the abolition of slavery, shall, without being printed or referred laid upon the table, and that no further action be had thereon.

A few weeks later, on February 6, 1837, John Quincy Adams, representative from Massachusetts and the former president of the United States, stated from his place in the House, “that he held in his hand a petition from twenty-two persons, declaring themselves to be slaves; and he wished to know whether the Speaker considered such a petition as coming within the resolution of the 18th of January.”

The anti-abolitionists in Congress responded with vigor. South Carolina’s representative, Waddy Thompson, Jr., proposed the following:

Resolved, That the Honorable John Quincy Adams, by the attempt just made by him to introduce a petition purporting on its face to be from slaves, has been guilty of a gross disrespect to this House, and that he be instantly brought to bar to receive the severe censure of the House.

The following day Rep. Thompson accepted a substitute to his motion, proposed by Rep. George Coke Dromgoole of Virginia:

Resolved that the Hon. John Q. Adams, a member of this House by stating that he had in his possession a paper purporting to be a petition from slaves, and inquiring if it came within the meaning of a resolution heretofore adapted, as preliminary to its presentation, has been given color to the idea that slaves have the right of petition, and of his readiness to be their organ, and that for the same he deserves the censure of this House.

Rep. Caleb Cushing spoke on behalf of his fellow Bay Stater, beginning his defense:

If, in the present contingency, any thing had transpired of itself tending to justify the resolution of censure, I could not fail to remember that he, who is the object of it, has presided over the destinies of my country; that he is at this moment a Representative, in common with myself, of the State of Massachusetts; that, eminent as he is by reason of his long public services, and the exalted stations he has held, he is yet more eminent for his intellectual superiority; that his character no longer belongs to his State or his country, but to the history of civilization and of liberty; and I would have members ponder well the case, before they proceed, whether to gratify friends or appease foes, to record their votes in censure of such a man.

Speech of Mr. J.C. Alford, of Georgia, on Abolition Petitions (1840)

By Julius Caesar Alford

The issue of abolition petitions remained unresolved, and in 1840, during the Twenty-sixth United States Congress, Georgia Rep. Julius Caesar Alford made an impassioned speech. He began:

Mr. Speaker: I am pleased that I have at last obtained the floor, and have an opportunity of expressing my views in this Hall on this most important question – a question to my constituents of the deepest interest; one that strikes at the existence of the Union.I will not evade the question. If my friend from South Carolina, (Mr. Thompson) does not intend by his proposition to reject the reception, I will offer an amendment that shall bring the question directly before the House, and compel this body to decide whether they will or will not receive these petitions…

I will meet this question at once on what its friends are pleased to call in this debate high constitutional grounds. Congress has no constitutional right or power to receive these abolition petitions; and let me say to gentlemen, in all truth and sincerity, that if they decide, in violation of that sacred instrument, that they shall be received, I will say to my constituents, from my heart and soul, that they have no longer any use for this Union. It will then be to them an engine of the most diabolical oppression.

For more information about The American Slavery Collection, 1820-1922, including pricing, or to request a trial for your institution, please contact readexmarketing@readex.com.