“Unspeakable joy sprung up in my soul”: The Camp Meeting Roots of the Chautauqua Movement

The Methodist Episcopal Church was the first and largest denomination to establish the practice of organizing outdoor religious worship. It originated in the wild frontier of Kentucky and quickly spread throughout the Mississippi Valley. The historian Herbert B. Adams described this evolution in a disquisition included in the 1896 annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. In laying out the educational and historical roots of Chautauqua, he wrote:

American summer schools of the Chautauqua type are historical evolutions of the Southern camp meeting….This first camp meeting was made necessary by a remarkable overflow of religious enthusiasm resulting from the evangelistic work of two Scotch-Irish brothers named McGee, one a Presbyterian and the other a Methodist, supported by the Rev. Mr. McGreedy, a local Presbyterian pastor, whose church proved too small to hold the gathering multitudes. Kentucky hunters and frontiersmen immediately mastered the situation by reverting to bivouacs and open-air meetings, such as Daniel Boone held under the great elm tree at Boonesboro. And thus on Red River a religious folkmote assembled day after day in the heart of the forest.

Adams continues:

The idea of utilizing the camp meeting for educational purposes, the thought of a “camp-meeting institute,” where methods of teaching should be cultivated, was suggested by Silas Farmer, the antiquary and historian of Detroit, Mich., in the Sunday School Journal, as early as April, 1870; but a similar and perhaps larger idea was early cherished by Lewis Miller, of Akron, Ohio, the inventor of the Buckeye mower, which has revolutionized the farming machinery of America. This practically minded, large-hearted, and wealthy man, who all his life had been actively engaged in Sunday-school work, and who was one of the earliest and stanchest [sic] promoters of mechanical and agricultural education in Ohio, joined hands with Dr. (now Bishop) John H. Vincent for the improvement of Sunday-school teaching by a generous alliance with science and literature. Dr. Vincent, for many years a leader in American Sunday-school work, believed most strongly in the increase of “week-day power” by the intimate association of secular and religious learning. He believed in the harmony of religion with everyday life. In the summer of 1873 the two men, Mr. Miller and Dr. Vincent, visited the Fourth Erie conference camp meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church, held at Fair Point, on Lake Chautauqua, in southwestern New York. They chose that Fair Point for a local establishment of “The Chautauqua Sunday-School Assembly.”

A compelling history and first-hand account of this form of worship is presented in “Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, the Backwoods Preacher” published in 1857.

Cartwright describes his ecstatic conversion at age 15 in 1801. It happened at a camp meeting organized as a part of the Revival of 1800.

To this meeting I repaired, a guilty, wretched sinner. On the Saturday evening of said meeting, I went, with weeping multitudes, and bowed before the stand, and earnestly prayed for mercy. In the midst of a solemn struggle of soul, an impression was made on my mind, as though a voice said to me, “Thy sins are all forgiven thee.” Divine light flashed all round me, unspeakable joy sprung up in my soul. I rose to my feet, opened my eyes, and it really seemed as if I was in heaven; the trees, the leaves on them, and everything seemed, and I really thought were, praising God. My mother raised the shout, my Christian friends crowded around me and joined me in praising God; and though I have been since then, in many instances, unfaithful, yet I have never, for one moment, doubted that the Lord did, then and there, forgive my sins and give me religion.

Soon after, he joined the Methodist Episcopal Church and began his long mission of converting thousands of people.

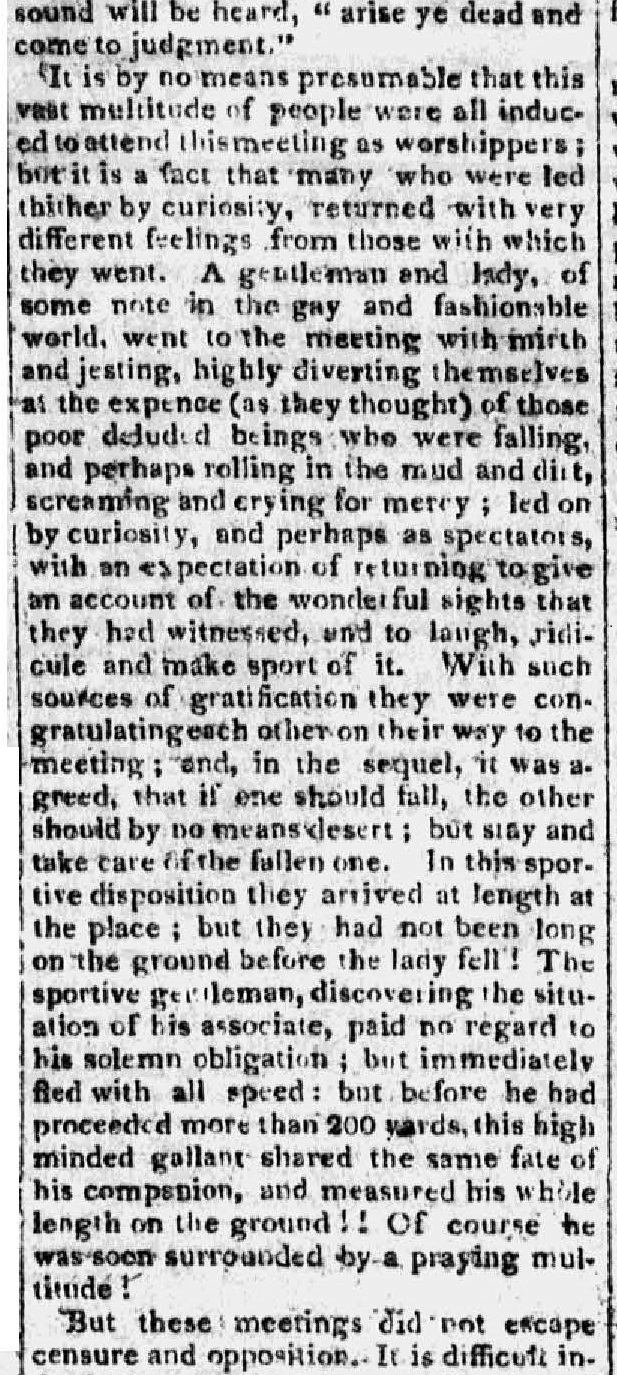

As the popularity of the camp meetings grew exponentially, so did criticism. Mass conversions were described where, under the influence of the exhorting preachers, hundreds, possibly thousands, fell to the ground writhing in ecstasy. A defender of the meetings, writing under the pseudonym Theophilus Arminius [Thomas Spottswood Hinde], wrote a column in the Methodist Magazine which was reprinted on August 11, 1819, by the Republican Farmer of Bridgeport, Connecticut. While defending absolutely the meetings, Hinde included lavish descriptions of a pair of mocking critics attending a meeting and getting caught up in the mysterious power. They attempted to flee but were time and again struck to the ground.

In this sportive disposition they arrived…but they had not been long on the ground before the lady fell! The sportive gentleman, discovering the situation of his associate, paid no regard to his solemn obligation; but immediately fled with all speed: but before he had proceeded more than 200 yards, this high minded gallant shared the same fate of his companion, and measured his whole length on the ground!!

In the same year Edward Sharman published a lengthy pamphlet titled “The Christian World Unmasked: or, An Enquiry into the Foundation of Methodist Camp-Meetings.”

In this work Sharman asks,

Are Methodist camp meetings then, from Heaven, or of men? Our answer to this question will decide on the propriety and legality of such religious assemblies. For, if they are of divine authority, they are universally binding on all christians [sic]. And Methodists deserve the reward of Christ’s faithful servants for meeting in the woods: while other sects do not the will of their heavenly master, merit his stripes for disobedience. But, if those lengthy meetings are an human invention, they ought to be treated as such and whatever in them is virtuous and orderly, it becomes christians to espy after; and those things that are erroneous and disorderly, they are bound to abandon as human errors.

“If we deviate ever so little from Scripture, (declares Mr. Wesley,) we are in danger of falling into enthusiasm every hour.”

Sharman makes his position clear:

Religious enthusiasm consists, as Mr. W. observes, in imaginary impressions and inspirations from God, and deludes men to think they are christians when they are not.

Another pamphlet, first circulated in 1807 with the title “A Poem; Written on a Methodist Camp-Meeting,” was republished in 1819 bearing a new title: “A Poetical Description of a Methodist Camp-Meeting.” The title page includes a short verse:

What dreadful tumults through the camp resound!

What pious souls be prostrate on the ground!

No author is credited. Throughout much of the 19th century, a common diagnosis for patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals was “religious mania.” In reference to the concept of religious mania, the writer of this pamphlet makes his opposition to camp meetings vivid in his “Introductory Observations”:

The power of religious fanaticism appears to be so great with some people, as to overpower the natural functions of the body. Hence we may account for the convulsions or jerkings of many who frequent the camp-meetings.

The poem itself is lengthy. It begins:

As folly bids her trumpets loudly sound,

And superstition spread her influence round;

Thousands at once the sounding calls obey,

And to the sylvan shades direct their way.

From their own homes to a sequester’d grove,

The mighty crowds in mighty numbers rove;

The thronging multitudes the forest gain,

And with their vocal thunders shake the plain.

Loud jarring tumults rend the limped air,

And fill the soul with wildness and despair;

Here towering frenzy spreads her dire alarms,

And reason stoops, opprest beneath her arms.

Another anonymous writer, published on December 12, 1832, by the Eastern Argus of Portland, Maine, took a similar attitude toward the demonstration of mania among many of those attending the two camp meetings he attended in Kentucky and Ohio. He describes the physical preparations at the Ohio camp.

Three sides were occupied by tents for the congregation, and the fourth by booths for the preachers. A little in advance before the booths was erected a platform for the performing preacher, and at the foot of this, inclosed [sic] by forms, was a species of sanctuary, called “the penitent’s pen.”

He also describes the behavior of the attendees and suggests reasons for their attendance.

People of every denomination might be seen here, allured by various motives. The girls, dressed in all colars [sic] of the rainbow, congregated to display their persons and costumes; the young men came to see the girls, and considered it a sort of “frolic;” and the old women induced by fanaticism and other motives, assembled in large numbers, and waited with patience for the proper season of repentance. At the intervals between the “preachments,” the young married and unmarried women promenaded round the tents, and their smiling faces formed a striking contrast to the demure countenances of their more experienced sisters, who, according to their age or temperament, descanted on the folly, or condemned the sinfulness of such conduct. Some of these old dames, I was informed, were decoy birds, who shared the profits with the preachers, and attended all the “camp-meetings” in the country.

The author returns to the “penitent’s pen,” writing:

After sunset the place was lighted up by beacon fires and candles, and the scene seemed to be changing to one of more deep and awful interest. About nine o’clock the preachers began to rally their forces—the candles were snuffed—fuel was added to the fires—clean straw was shook in the “penitent’s pen” and every moment “gave dreadful note of preparation…

And then the preacher began:

…he bellowed—he roared—he whined—he shouted until he became actually hoarse, and the perspiration rolled down his face. Now, the faithful seemed to take the infection, and as if overcome by their excited feelings, flung themselves headlong on the straw into the penitent’s pen—the old dames leading the way. The preachers, to the number of a dozen, gave a loud shout and rushed into the thick of the penitents. A scene now ensued that beggars all description. About twenty women, young and old, were lying in every direction and position, with caps and without caps, screeching, brawling, and kicking in hysterics, and profaning the name of Jesus….The scene altogether was highly entertaining, penitents, parsons, caps, combs, and straw, jumbled in one heterogeneous mass, lay heaving on the ground, and formed at this juncture a grouping that might be done justice to by the pencil of Hogarth, for the pen of the author of Hudibras [Samuel Butler], but of which, I fear an inferior pen or pencil must fail in conveying an adequate idea….

The women were occasionally making confessions, pro bono publico, when sundry “backslidings” were acknowledged for the edification of the multitude.

Over the ensuing years the camp meetings grew into established summer resorts, of a sort. The tents disappeared, replaced by cottages and tabernacles. Report of ecstatic conversions faded. A new attitude was developing. It was captured in an article in the Indianapolis Sentinel issue of July 16, 1873.

The Methodist Camp Meetings.—A correspondent of the Long Branch Daily News complains that “the most of people pack their religion along with their winter clothing, in their trunks, not to be taken out till the coming season. The mass of religious life in professors of all denominations will only bear the feeblest possible strain in warm weather.” To this the Golden Age says: Probably it is a discovery of this peculiarity of human nature which has led the Methodists (who are a wise people in their generation) to establish camp-meetings on a large scale, so as to combine the pleasure and change of air sought for in summer resorts, with the sermons and prayer meetings which are not so much in demand in hot weather.

The writer describes the evolution of the campground on Martha’s Vineyard “from a struggling little town to one of the most favorite watering places in the country.” He extols the improvements made by Methodist camp meeting associations, and he lauds other camps in the region. He concludes:

If this union of piety and pleasure is not a good one, let some sourpuss old Puritan, who believes only in piety and misery as fit yoke fellows, forbid the bans. For our part we congratulate the newly-wedded pair, and wish them God speed.

Nevertheless, there was dissension among the clergy. On September 30, 1874, the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer reported on unanimously adopted resolutions at the local Methodist Episcopal Preachers’ Meeting. They concerned camp meetings and the Fourth Commandment: “Remember the Sabbath-day, to keep it holy.” Further, the resolutions asserted that the commandment applies to all people, apparently Christian or not. They are enjoined to observe the day “by not doing their own ways, nor finding their own pleasure, nor speaking their own words; but by making the Sabbath a delight, the holy of the Lord, honorable, and by abstaining utterly from secular pursuits, works of necessity and mercy only excepted.” Possibly, these men embody the “sourpuss old Puritan” referred to previously. They conclude:

That we condemn all Sabbath desecration connected with camp-meetings, such as charging admission fees at the gates, selling soda-water, lemonade, ice-cream, etc., making merchandise of the Lord’s-day.

Despite criticisms both within the denomination and without, camp meetings enjoyed enormous public approbation for several more decades. Eventually, attendance flagged, and what was broadly understood to be the essential purpose of the meetings, conversion, became infrequent. At a meeting of Methodist preachers in Worcester, Massachusetts, on December 14, 1903, those present debated the future of the camps. It was reported in the Worcester Daily Spy the next day: “…the speakers paid special attention to the decline in interest and attendance at the camp meeting.”

A paper was presented titled “What Shall We Do With the Camp Meeting?” The reverend recalls his own conversion at a meeting, ruing the decline in their popularity:

“When the camp meeting was a great factor in church work, a quarter of a century ago, ministers planned for the meetings weeks and months ahead.” he said. “In those days minsters went to the camp and stayed the entire week instead of just remaining there long enough to deliver a speech and leave on the next train for some seashore resort.”

He yearns for the “old enthusiasm” but warns “unless the only important part of Methodism is teaching divine truths to women and children the meetings can not be cherished.” During the ensuing discussion of t he paper differences of opinion were offered. One participant opined:

…25 or 50 years ago the camp meetings were something for excitement, as it were, and the unconverted attended them and were reached by exhortation. In the present age the unconverted go to pleasure parks, trolley riding and hundreds of other places instead of camp meetings. Those who attend camp meetings are already converted so the result is not the same.

It seemed the paper had identified the challenges to camp meetings. The fortunes of this century-old institution were ebbing as the American public embraced the many allurements and new entertainments of the modern age. Among these diversions, the growing Chautauqua Movement was becoming an increasingly attractive replacement.