“Like all other people, forbearance with them will cease to be a virtue…”: The Nez Perce Treaty of 1863

This is the fifth in a series of blog articles highlighting primary source content from the Readex Native American Tribal Histories collection. The articles in this series offer further insight and added perspectives into westward expansion, the Trail of Tears, the history of Manifest Destiny, and the impacts to Native Americans.

On June 9, 1863, several chiefs of the Nez Perce nation signed a treaty with representatives of the United States government – their second treaty with the United States. The first was a treaty in 1855 with Isaac I. Stevens, first governor of Washington Territory. The Nez Perce traditionally held territory throughout present-day Washington and Idaho. White settlers poured into the region in the years following the 1855 treaty, and local agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs were either unable or unwilling to enforce Nez Perce territorial boundaries against their incursions. In addition, many of the promised annuities of the 1855 treaty never materialized. Unlike the 1855 treaty which had been signed by every chief of the tribe, a significant number of Nez Perce leaders refused to sign the treaty of 1863. While relations between the Nez Perce and the United States had already become strained by the failures of the 1855 treaty, the events of the next several years would damage that relationship even further and drive a political wedge through the Nez Perce.

The treaty of 1863 was in many ways an unremarkable example of its type; it drastically reduced Nez Perce territory, confined the tribe to a reservation, and promised annuity payments and services for several years during which time the Nez Perce were expected to adopt ranching and agricultural practices and become self-sufficient in a lifestyle respected by whites. Article 1 decreed that the Nez Perce would relinquish all their territory, except as defined by Article 2. Article 2 laid rough boundaries for the reservation, which were to be surveyed and marked. Whites were not to reside on the reservation without the express consent of the tribe and their agent, and the Nez Perce were required to remove to the reservation within one year after the United States ratified the treaty. Article 3 stipulated that the proposed reservation be surveyed immediately after ratification, while Article 4 outlined annuity payments for the Nez Perce, many of which were contingent upon the treaty being ratified by the United States government.[i] In fact, the 1863 treaty with the Nez Perce would not be ratified until 1867, leaving the tribe in legislative limbo for four long years.

Even had it been ratified immediately, the treaty was not without its flaws. In a letter to William P. Dole – Commissioner of Indian Affairs – in October of 1863, Calvin H. Hale – Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Washington Territory – wrote,

There are instances, where both the treaty stipulations & the amounts appropriated, are totally inadequate, to accomplish the proposed objects… It is impossible, that the work proposed, should, under any circumstances be done for that price… So far as I have been able to ascertain nothing has been done at any of the Reservations, even preparatory, to this portion of the agreement, except in the case of the Nez Perce Chief, where I have directed the Agent to provide a house for Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot].[ii]

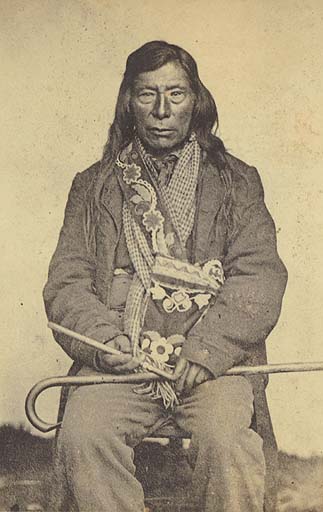

Hallalhotsoot – called “Lawyer” by Indian agents – was the primary chief of the Nez Perce, and a staunch advocate for continued friendship with the United States. Unfortunately, repeated failures by the government and local agents to uphold the promises of the treaties would place Hallalhotsoot in an increasingly untenable position with many of the other chiefs of his tribe.

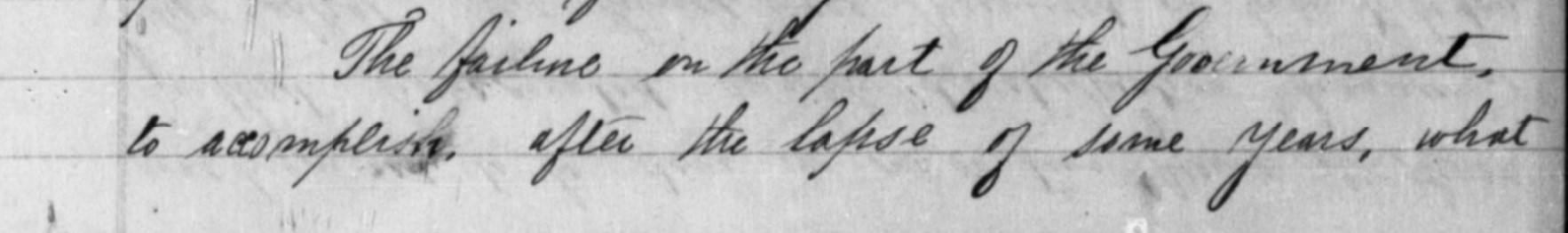

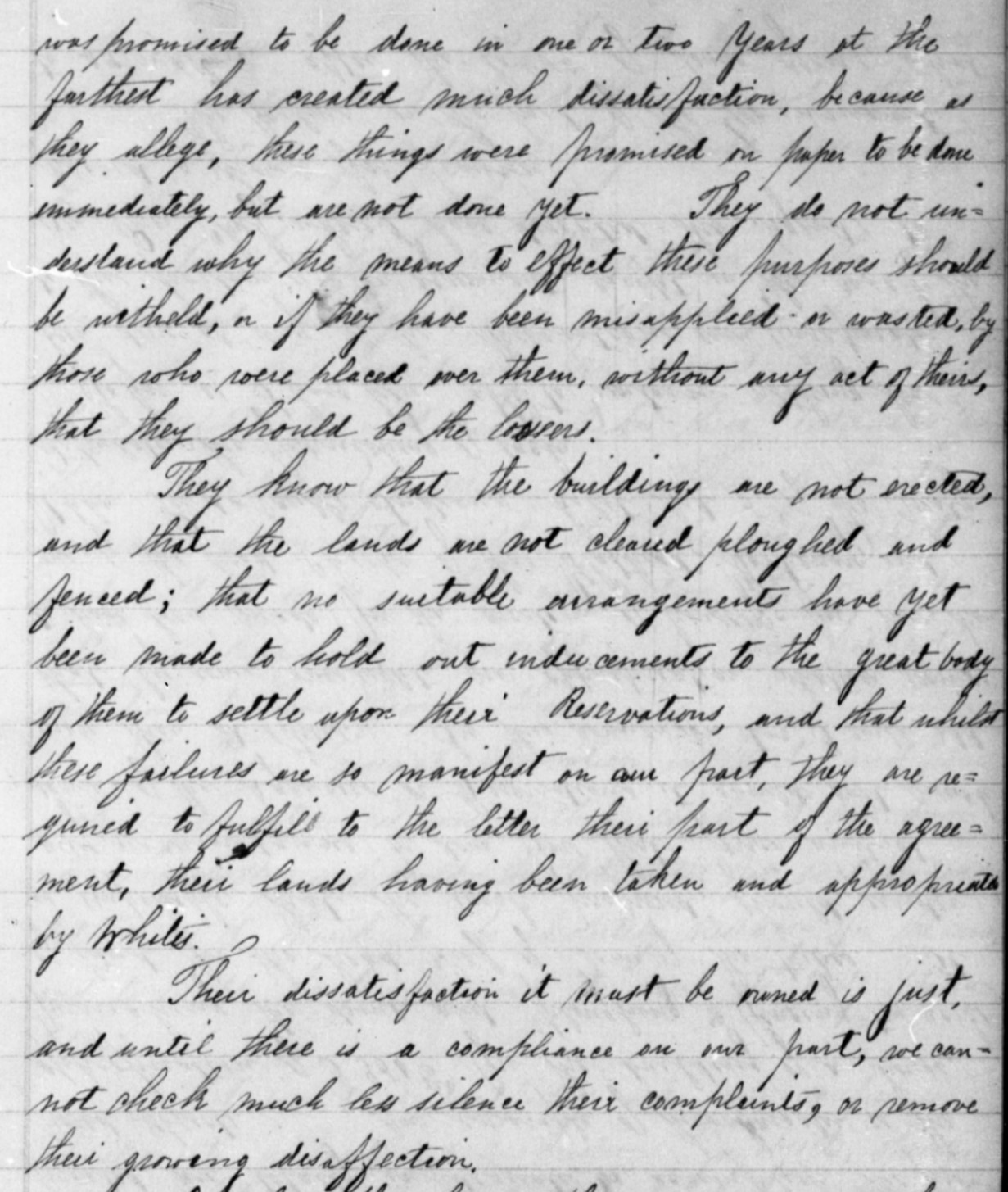

Superintendent Hale went on to highlight other problems, particularly concerning the failure of the United States to honor the stipulations of the 1855 treaty;

The failure on the part of the Government to accomplish, after the lapse of some years, what was promised to be done in one or two years at the farthest has created much dissatisfaction, because as they allege, these things were promised on paper to be done immediately, but are not done yet. They do not understand why the means to effect these purposes should be withheld, or if they have been misapplied or wasted, by those who were placed over them, without any act of theirs, that they should be the loser. They know that the buildings are not erected, and that the lands are not cleared ploughed and fenced; that no suitable arrangements have yet been made to hold out inducements to the great body of them to settle upon their Reservations, and that whilst these failures are so manifest on our part, they are required to fulfill to the letter their part of the agreement, their lands having been taken and appropriated by whites. Their dissatisfaction it must be owned is just, and until there is a compliance on our part, we cannot check much less silence their complaints or remove their growing disaffection.[iv]

Hale’s warnings went unheeded, and nothing more was said of the Nez Perce treaties until 1866, when David W. Ballard took office as the governor of Idaho Territory, where the Nez Perce reservation was now located. In a letter to Dennis N. Cooley – Commissioner of Indian Affairs – Ballard stated,

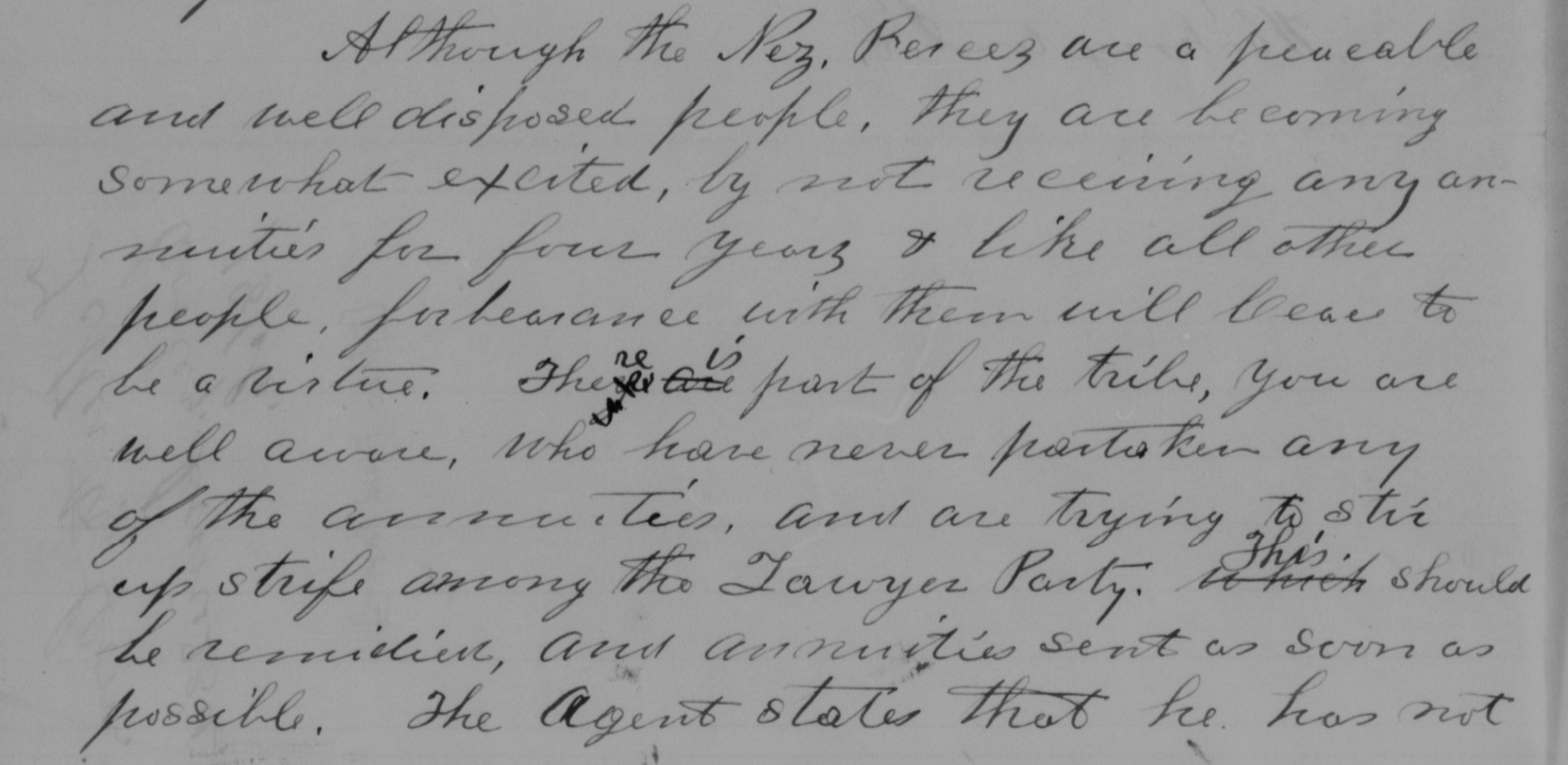

Although the Nez Perce are a peaceable and well disposed people, they are becoming somewhat excited, by not receiving any annuities for four years [emphasis mine] and like all other people, forbearance with them will cease to be a virtue. There is part of the Tribe, you are well aware, who have never partaken any of the annuities, and are trying to stir up strife among the Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot] Party. This should be remedied, and annuities sent as soon as possible.[v]

Annuity payments were a vital lifeline for Native American tribes cut off from access to both white markets and their traditional lifestyles. And, Ballard’s worries were apparently confirmed when he wrote the Commissioner again in September 1866 to say,

I am unofficially informed from a reliable source that the Nez Perce Indians have become dissatisfied with the provisions of the treaty of 1863 and are now insisting on the provisions of the treaty of 1855 being carried out.

This was an especially poor turn of events in Ballard’s opinion:

As from advice recently received from your office, I am expected at an early period to lay before these Indians an amended copy of the treaty of 1863, for their ratification…[vi]

More than three years had passed since the 1863 treaty had been signed by the Nez Perce, and it was only now amended and returned for their approval. When Cooley sent Ballard the proposed amendments in early November 1866, they did nothing to address the failures of the 1855 treaty, or the unpaid annuities of the previous four years, but instead proposed,

…the said tribe hereby consent that upon the public roads which may run across the reservation, there may be established, at such points as shall be necessary for public convenience, hotels or stage stands, with a reasonable quantity of land adjacent thereto for pasturage and agricultural purposes, as shall be recommended by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and approved by the Secretary of the Interior.

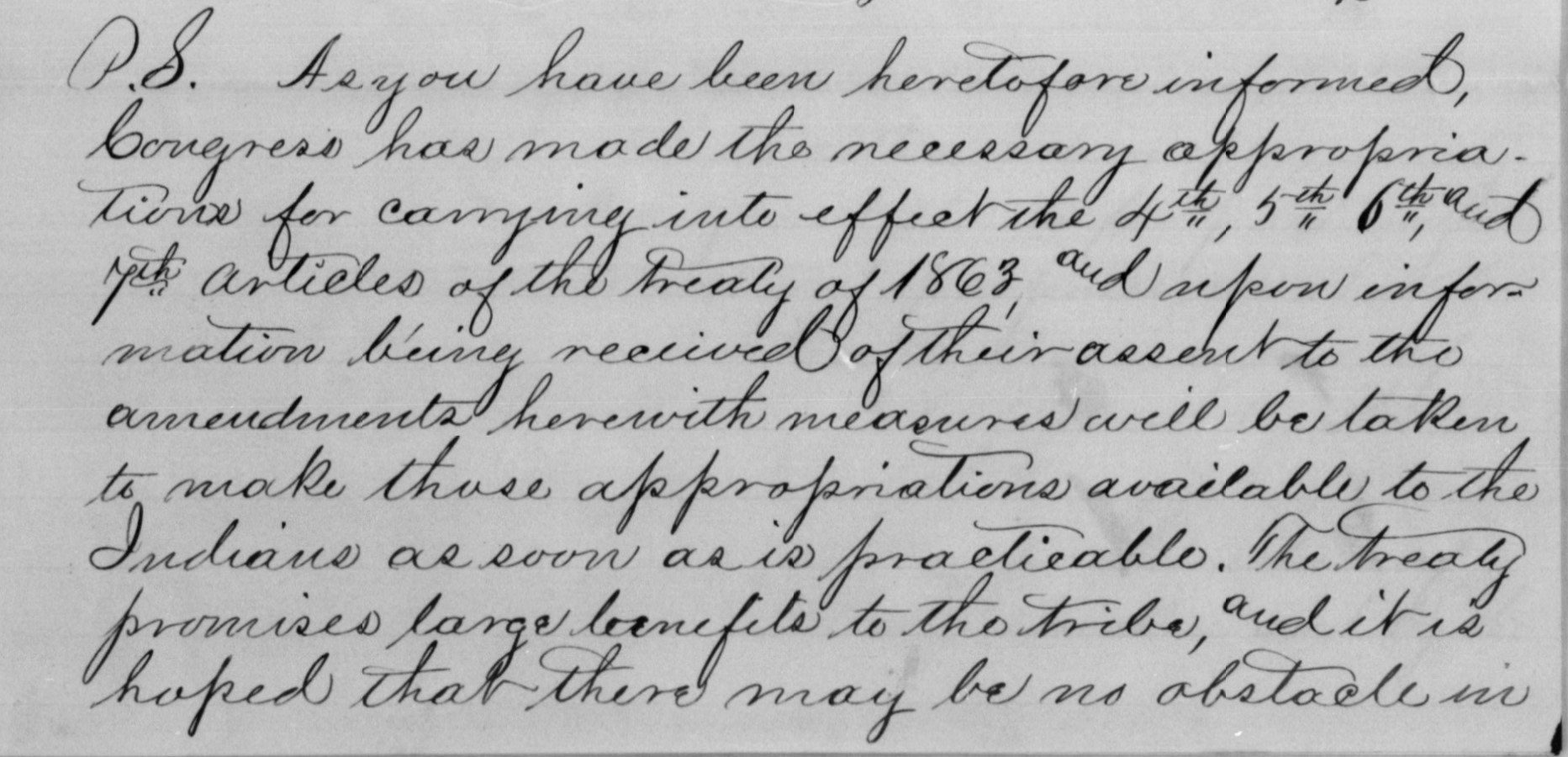

As if to add insult to injury, the Commissioner included a postscript to Ballard, which clarified the terms of amendments;

As you have been heretofore informed, Congress has made the necessary appropriations for carrying into effect the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th Articles of the treaty of 1863, and upon information being received of their assent to the amendments [emphasis mine] herewith measures will be taken to make those appropriations available to the Indians as soon as is practicable. The treaty promises large benefits to the tribe, and it is hoped that there may be no obstacle in the way of their enjoyment of those benefits.[vii]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, local agent James O’Neil wrote to Governor Ballard that December to inform him,

Our council with the Nez Perce Indians closed to day and I regret to say without being able to obtain the assent of the Indians to the amendments… The Nez Perce were not only unwilling to concede their demands but had been promised better terms by the previous governor of Idaho Territory, Caleb Lyon; who had told the Nez Perce…that the treaty which had been made with them by Hale Howe and Co. was not a good one and that he had received instructions to call them together and make another treaty with them by which they would obtain all the land granted them by the Stevens and Palmer treaty of 1855…[viii]

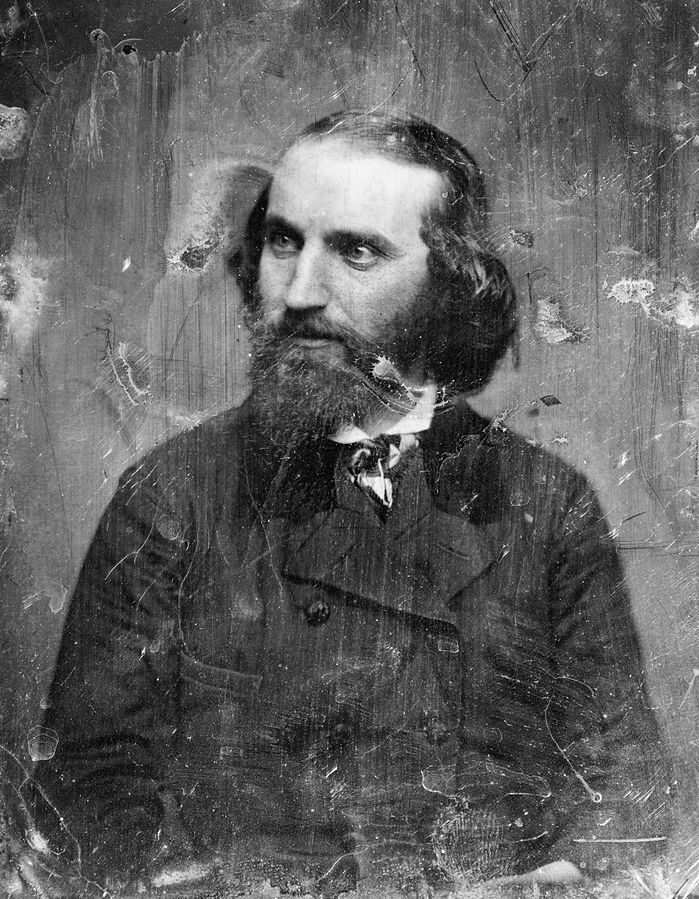

It is worth taking a moment to discuss Caleb Lyon’s tenure as territorial governor of Idaho, as unrealized promises of better treaties were not the only consequence of Lyon’s time in office. In a speech given at a council with the Nez Perce in June 1867, David W. Ballard, Lyon’s successor, said,

…a considerable portion of the annuities due you, was appropriated by Congress, while his Excellency, Caleb Lyon, of Lyonsdale, was the Governor and Ex Officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs of Idaho. What became of these funds I cannot say.[ix]

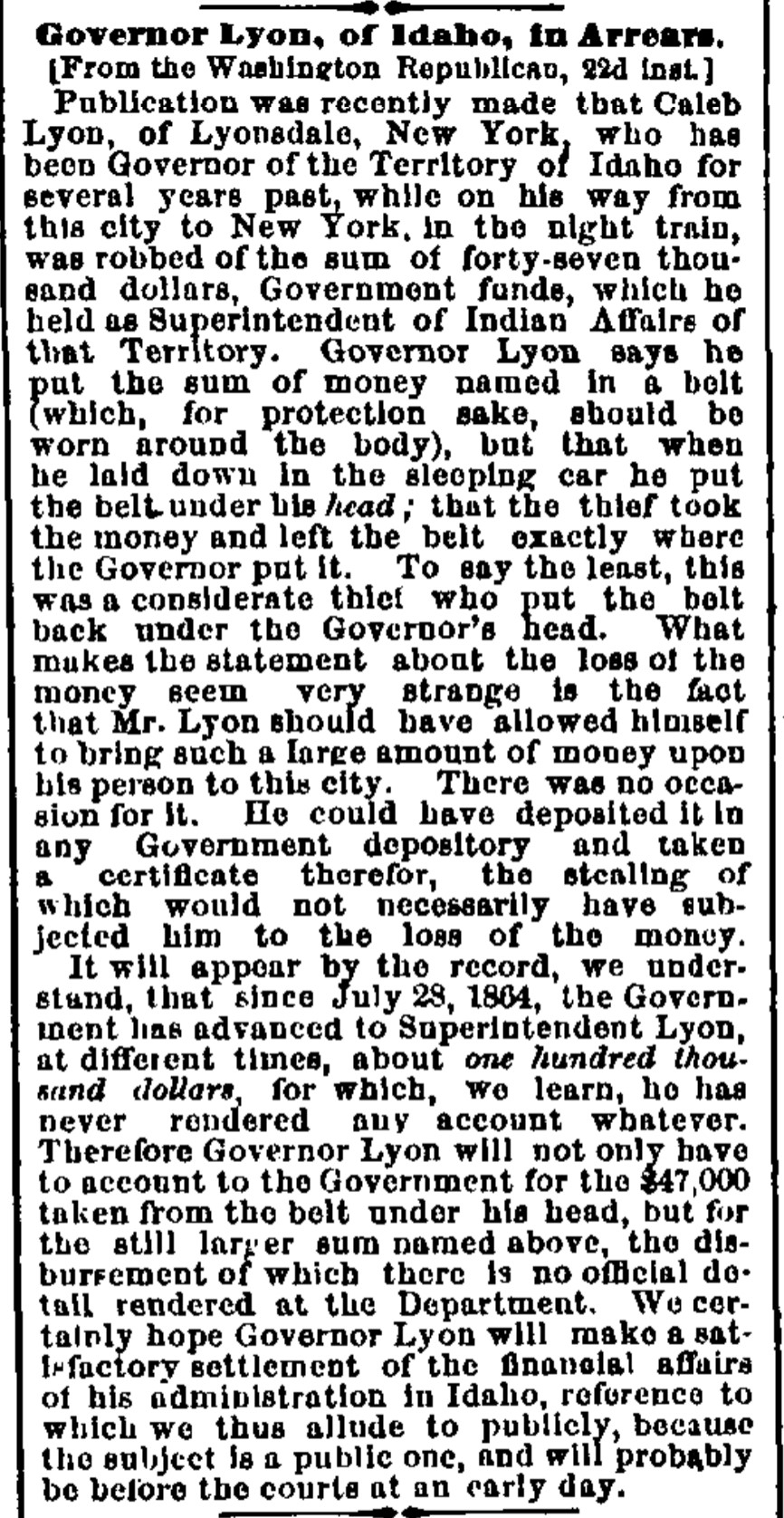

In December of 1866, shortly after leaving his post as territorial governor, Lyon appeared in the newspaper Chicago Daily Tribune because he,

…was robbed of the sum of forty-seven thousand dollars, Government funds, which he held as Superintendent of Indian Affairs of that Territory. Governor Lyon says he put the sum of money named in a belt (which, for protection sake, should be worn around the body), but that when he laid down in the sleeping car he put the belt under his head; that the thief took the money and left the belt exactly where the Governor put it. To say the least, this was a considerate thief who put the belt back under the Governor’s head.

The Tribune article went on to wonder at Lyon’s choice to transport the money personally, when,

He could have deposited it in any Government depository and taken a certificate therefor…and further, the Government has advanced to Superintendent Lyon, at different times, about one hundred thousand dollars, for which, we learn, he has never rendered any account whatever. [x]

Local Indian Agent James O’Neil was rather more direct in his criticism in his annual report in July 1867, in which he wrote,

…promises made them [the Nez Perce] by Gov. Lyon that it [the 1863 treaty] would not be ratified and that he was authorized to make a new treaty with them by which they would retain all of their country as given them under the Treaty of 1857 [sic 1855] except the site of the town of Lewiston, they had also been informed in March 1866 that Gov. Lyon would be here in the June following to pay their back annuities due under the treaty of 1855, the failure to carry out these promises and the idea they have that the stipulations of the treaty of 1863 will be carried out in the same manner is one of the causes of their bad feeling …if there is the same delay in carrying out the stipulations of the treaty of 1863 that there has been in that of 1855, some of the chiefs with their bands will join the hostile Indians…[xii]

While the 1863 treaty was ratified in April 1867, the situation had deteriorated so much that even Hallalhotsoot – previously the United States’ best ally among the Nez Perce – was growing impatient. In a letter to Governor Ballard in November 1866, James O’Neil wrote,

… Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot] and I have had a little talk, he says he wishes you would write to Washington and have them hurry up that treaty his chiefs are blaming him a great deal in regard to the treaty saying that he is selling their country without letting them know anything about it, he fears that it will yet result in a further division of the tribe. Some of the chiefs of influence too – Timothy, Levi George and others on the “El-pow-a-wai” owing to their disaffection refuse to come to the agency…[xiii]

And in June 1867 Special Indian Agent George Hough wrote that even the ratification of the treaty had not satisfied Hallalhotsoot;

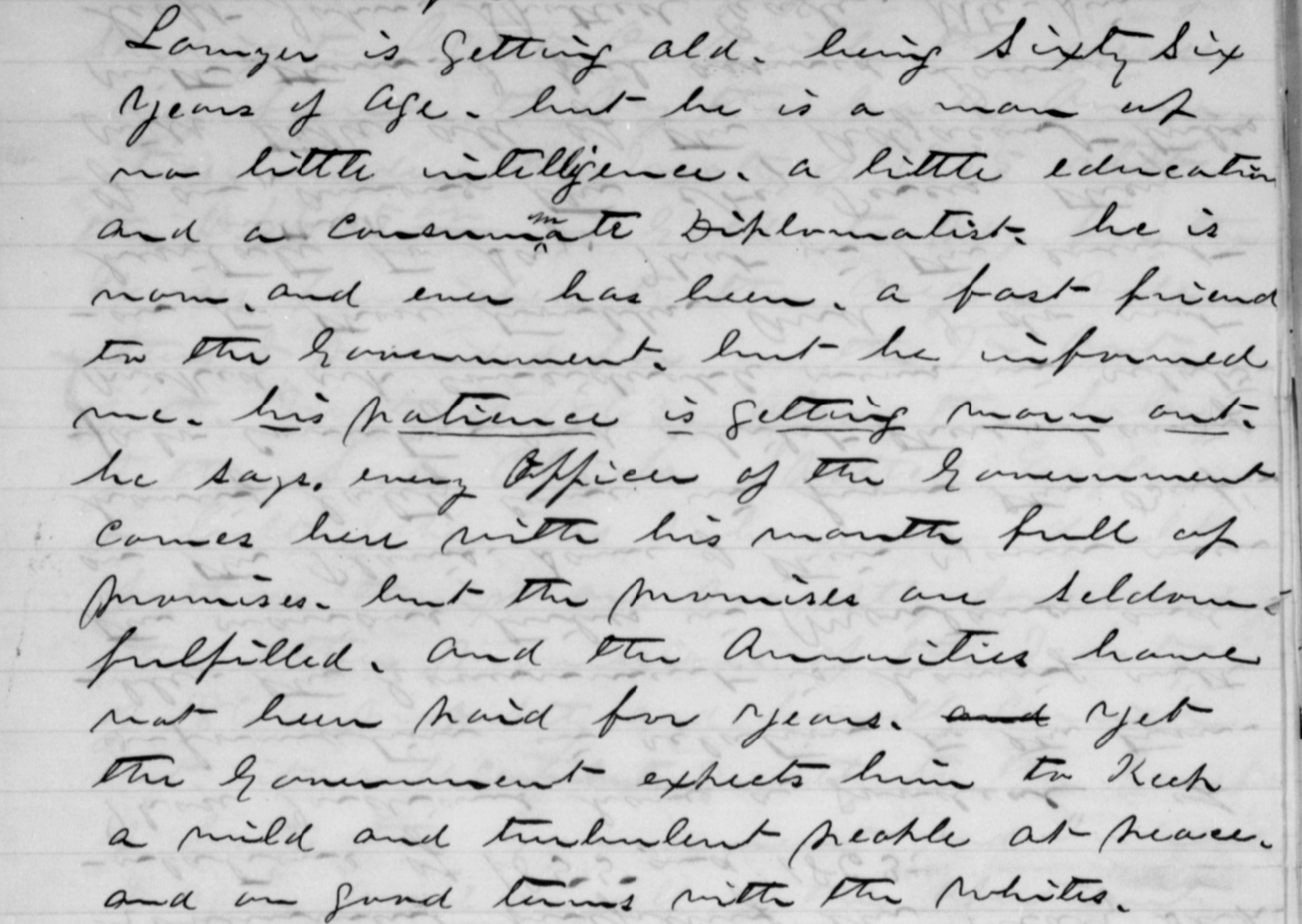

Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot] is getting old, being sixty six years of age, but he is a man of no little intelligence, a little education, and a consummate diplomatist, he is now, and ever has been, a fast friend to the Government, but he informed me, his patience is getting worn out. He says, every Officer of the Government comes here with his mouth full of promises but the promises are seldom fulfilled, and the annuities have not been paid for years, yet the Government expects him to keep a wild and turbulent people at peace and on good terms with the whites.[xiv]

Hough continued,

Those Indians have a good deal of information in relation to the trouble the Government is having with the various tribes in Montana and on the Plains. Some of their young men having lately come in from the Buffalo Country, and whilst there, having wicked up considerable news in relation to those troubles, and I do not hesitate to say, that in the event of an attack among the Nez Perce, they will take all of the adjacent tribes with them…I again urge upon the Department the absolute necessity of immediately sending to Agent O’Neill the necessary funds to pay the back annuities under the Treaty of 1855 also the $4665.00 in Gold.[xv]

Agent James O’Neil also expressed concern that the Nez Perce might become openly hostile. In his annual report to Governor Ballard dated July 10, 1867, O'Neil wrote,

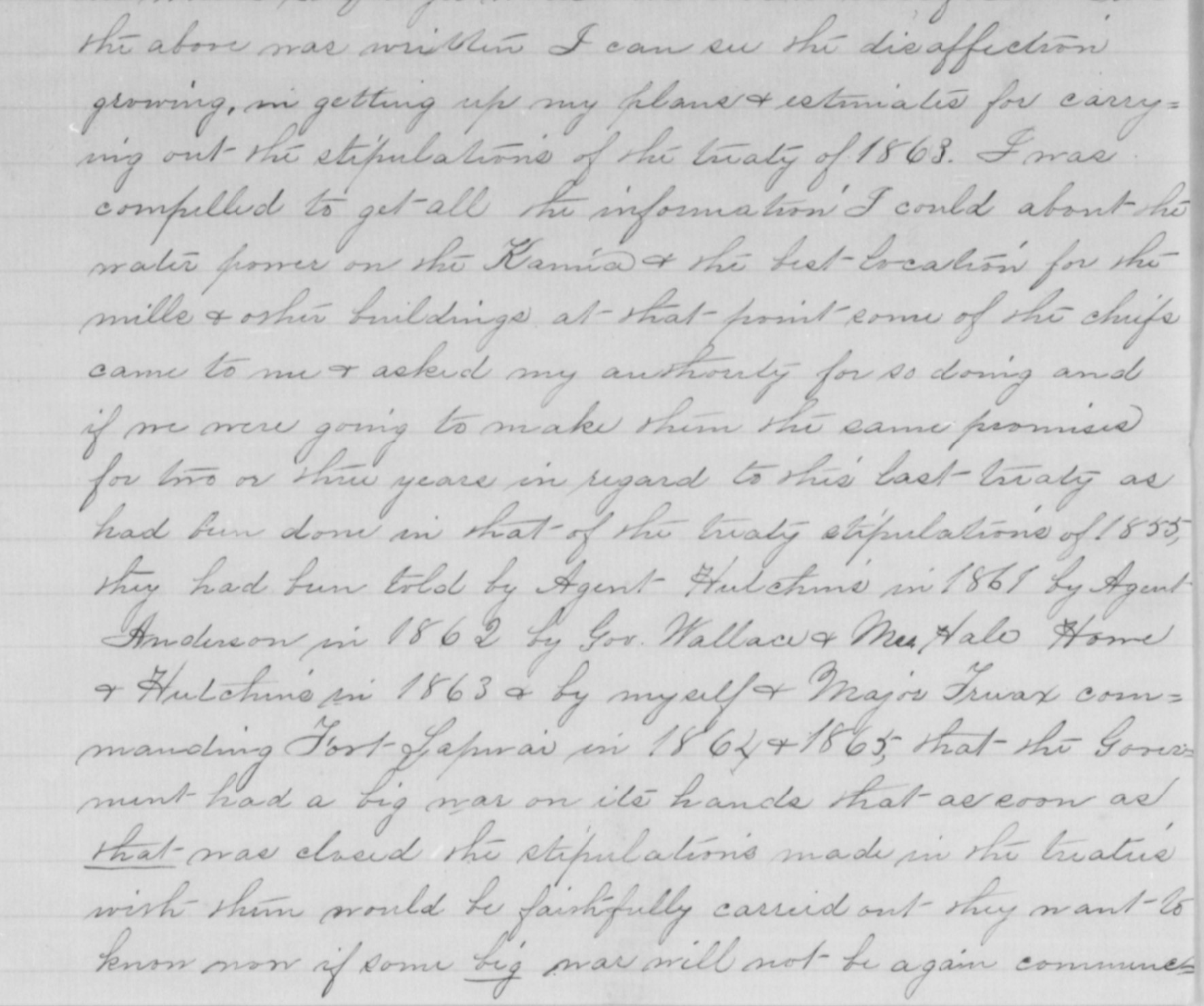

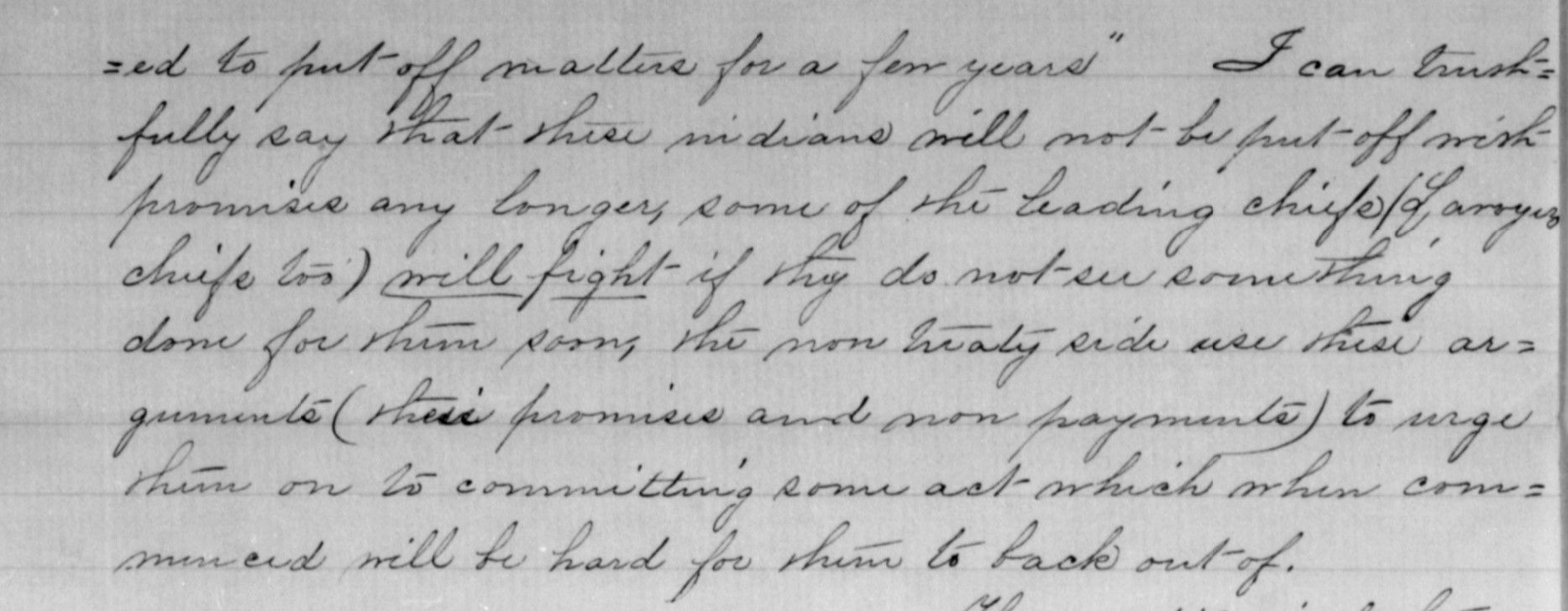

…I can see the disaffection growing, in getting up my plans & estimate for carrying out the stipulations of the treaty of 1863, I was compelled to get all the information I could about the water power on the Kamia & the best location for the mills & other buildings at that point some of the chiefs came to me & asked my authority for so doing and if we were going to make them the same promises for two or three years in regard to this last treaty as had been done in that of the treaty stipulations of 1855, they had been told by Agent Hutchins in 1861, by Agent Anderson in 1862 & by myself & Major Truax commanding Fort Lapwai in 1864 & 1865, that the Government had a big war on its hands [U.S. Civil War, 1861-1865] that as soon as that was closed the stipulations made in the treaties with them would be faithfully carried out they want to know now if some big war will not be again commenced to put off matters for a few years. I can truthfully say that these Indians will not be put off with promises any longer, some of the leading chiefs (Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot] chiefs too) will fight if they do not see something done for them soon, the non treaty side uses these arguments (these promises and non payments) to urge them on to committing some act which when commenced will be hard for them to back out of.[xvi]

O’Neil’s and Hough’s concerns were well-founded; at the end of August 1867, O’Neil wrote to Ballard,

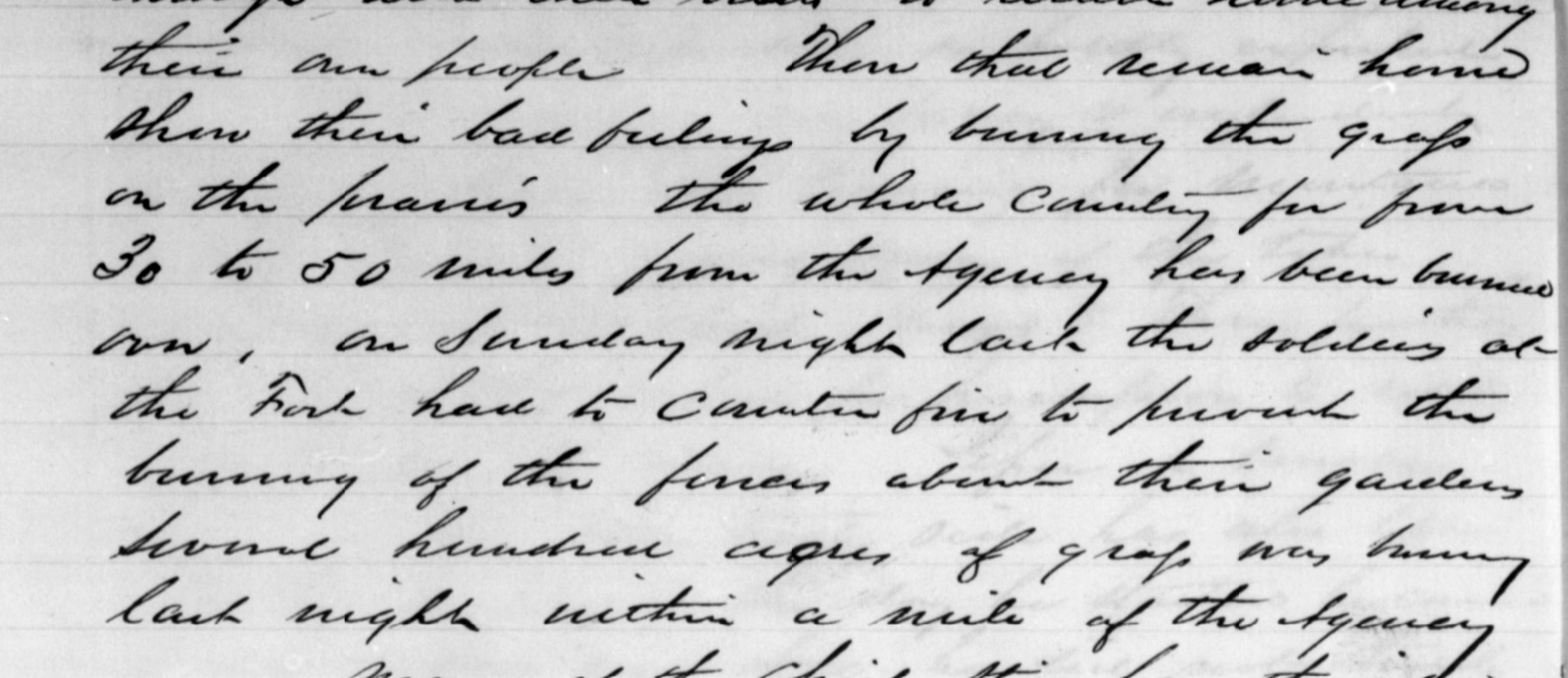

I have never since I have been among them seen their dissatisfaction so boldly expressed they are becoming very saucy & impudent many of them are leaving for mountains mostly however young men of the tribe some few of the chiefs “George” & “Three Feathers” (Lawyer [sic Hallalhotsoot] chiefs) asked for permission to visit their Flathead friends.” Groups of Nez Perce were leaving the reservation to “visit” neighboring tribes, both with and without Agent O’Neil’s permission, and those who remained “…have shown their bad feelings by burning the grass on the prairies. The whole Country for from 30 to 50 miles from the Agency has been burned over, on Sunday night last the soldier at the Fort had to counter fire to prevent the burning of the fences about their gardens several hundred acres of grass was burned last night within a mile of the Agency.[xvii]

This fractious state of affairs would continue for the next several years, as the Bureau of Indian Affairs tried to smooth over Nez Perce grievances with only marginal success.

[i] [Memorandum of Treaty with the Nez Perce, June 9, 1863]

[ii] [Letter from Calvin H. Hale to William P. Dole, Oct. 10, 1863]

[iii] Nez Perce man named Chief Lawyer, ca. 1861. 1861, University of Washington Libraries. Special Collections Division.

[iv] [Letter from Calvin H. Hale to William P. Dole, Oct. 10, 1863]

[v] [Letter from David W. Ballard to Dennis N. Cooley, June 23, 1866]

[vi] [[Letter from David W. Ballard to Dennis N. Cooley, Sept. 17, 1866]

[vii] [Letter from Dennis N. Cooley to David W. Ballard, Nov. 9, 1866]

[viii] [Letter from James O'Neil to David W. Ballard, Dec. 29, 1866]

[ix] [Proceedings of Council Held with Nez Perce Indians by David W. Ballard, June 17, 1867]

[x] Chicago Daily Tribune, 29 Dec. 1866, p. 4. Readex: Readex AllSearch

[xi] Brady, Matthew B. [Caleb Lyon, head-and shoulders portrait, three-quarters to the left, with beard]. [between 1844 and 1860]. Daguerreotype collection (Library of Congress).

[xii] [Annual Report from James O'Neil to David W. Ballard, July 10, 1867]

[xiii] [Letter from James O'Neil to David W. Ballard, Nov. 13, 1866]

[xiv] [Letter from George C. Hough to Nathaniel G. Taylor, June 27, 1867]

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] [Annual Report from James O'Neil to David W. Ballard, July 10, 1867]

[xvii] [Letter from James O'Neil to David W. Ballard, Aug. 31, 1867]

Other blogs in this series:

- Part 1: Native Removal Prior to the Indian Removal Act of 1830

- Part 2: Nineteenth Century Treaties with Native American Nations

- Part 3: “For the Great Father is angry, and will certainly hunt them down…”: Native American Wars Against United States Expansion

- Part 4: “We hope that henceforth we will be able to obtain our rights”: Native Political Pressure in the Nineteenth Century

Visit the Readex Native American Tribal Histories page for information on this collection and to request a complimentary trial.